Comments

- No comments found

It seems obvious that the COVID-19 pandemic must be worse in lower-income countries.

After all, it seems as if the opportunities for social distancing must be lower in urban areas in those countries, and the resources for everything from protective gear to hospital care must be lower. There are certainly cases where the pandemic has hit some areas hard outside of high-income countries: for example, the current situation in India, or the city of Manaus in Brazil that suffered a a first wave, and then suffered a second wave with a new variant of COVID.

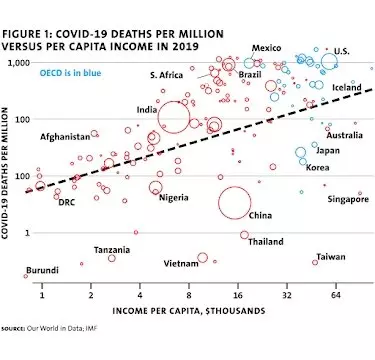

But that said, Angus Deaton (Nobel '15) makes a case that the areas outside the high-income countries of the world have, as a group, been less affected by the pandemic in "Covid-19 and Global Income Inequality" (Milken Institute Review, Second Quarter 2021, pp. 24-35). As a starting point for his argument, consider this figure, which shows countries with higher per capita income have tended to have higher per capita COVID-19 deaths.

Deaton discusses this figure from a variety of angles, including the possibility that COVID-19 is less well-measured in lower-income countries. But he argues that a number of other factors may help to explain the pattern of higher COVID-19 deaths in higher-income countries.

The low number in low-income countries has been linked by Pinelopi Goldberg and Tristan Reed to (the lack of) obesity, to the smaller fraction of the population over 70 and to the lower density of population in the largest urban centers.

Another alternative is to focus on demography. Patrick Heuveline and Michael Tzen provide age-adjusted mortality rates for each country by using country age-structures to predict what death rates would have been if the age-specific Covid-19 death rates had been the same as the U.S. The ratio of predicted deaths to actual deaths is then used to adjust each country’s crude mortality rate. This procedure scales up mortality rates for countries that are younger than the U.S. (Peru has the highest age- and sex-adjusted mortality rate) and scales down mortality rates for countries like Italy and Spain (which had the highest unadjusted rate) that are older than the U.S.

If Figure 1 were redrawn using the adjusted rates, the positive slope would remain, though the slope showing the relationship between death rates and income would be reduced from 0.99 to 0.47 — that is, the relationship would hold but would be less pronounced. ...

[P]oor countries are also warmer countries, where much activity takes place outside, and there are relatively few large, dense cities with elevators and mass transit to spread the virus. It is also possible that Africa’s long-standing experience with infectious epidemics stood it in good stead during this one. People in countries with more-developed economies consume a higher fraction of income in the form of personal services, which makes infection easier.

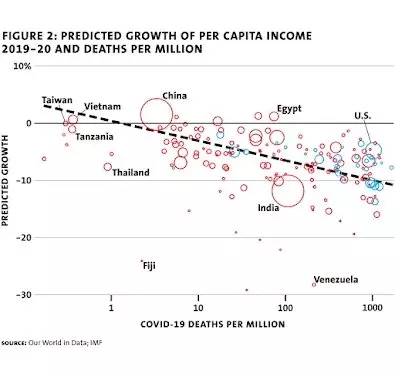

Deaton further argues that countries with higher death rates, as shown in the figure above, have also tended to have worse economic outcomes.

All analysis of the pandemic is, as yet, incomplete. Deaton's data goes through the end of 2020. Just as India has recently been clobbered by the pandemic, something similar could happen in other countries. Furthermore, in the poorest countries of the world, even a smaller loss of income may cause extreme human suffering.

But other possible lessons here are that, just perhaps, the pandemic did not make the world a more economically unequal place. Moreover, having lower deaths from the pandemic appears to be a good way of bolstering a country's economy.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest