Comments

- No comments found

About a decade ago, a concern emerged that China was dominant in global production of what are called “rare earth elements”–including notably yttrium, neodymium, europium, terbium, and dysprosium. (Giving the atomic number for each of these is left as an exercise for the reader.) These materials are, at least with current technology, essential for manufacturing certain clean energy technologies, like components of electric vehicles and wind turbines, as well as some materials used in defense-related technologies, like permanent magnets and certain coatings for jet engines.

In a post back in 2015, I pointed out that China had been making threatening sounds about refusing to export these materials, but also that the market had been reacting to that threat by figuring out how to conserve on the demand side and how to find alternative sources and recycle on the supply side. A group of researchers from the Rand Corporation–Fabian Villalobos, Jonathan L. Brosmer, Richard Silberglitt, Justin M. Lee, and Aimee E. Curtright– provide an updated view of the situation in “Time for Resilient Critical Material Supply Chain Policies” (2022).

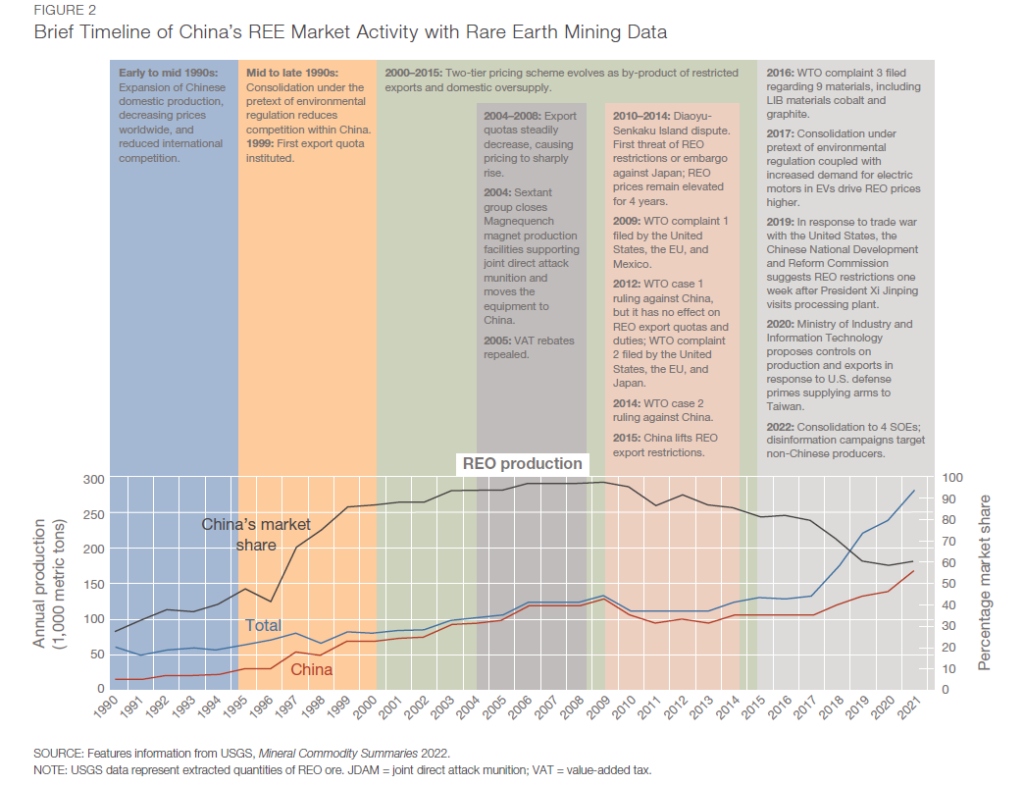

Here’s a figure offering a timeline of events. Focus your attention on the graph at the bottom, which refers to production of REOs, or “rare earth oxides,” which is the amount produced after the ore has been refined. From about 1998 up through 2013, more than 90% of the rare earths being produced originated from mines in China (black line). This was the period when China was threatening to limit or cut off supplies to the rest of the world. But starting around 2016, global mining of rare earths rose substantially (red line), while mining in China rose much less (blue line). China’s market share of rare earth elements remains high, but has now fallen to about 55%.

The Rand researchers emphasize that China’s market share remains large, but they also make the point that China’s share of processing these rare earth elements is even larger–a legacy of the years when China was almost the only global producer. They write:

Current production and processing activities demonstrate that China’s window for disruption of these critical material supply chains may be narrowing, but not eliminated, and remains a strategic geopolitical tool for its leadership. …

As shown in Figure 2, China’s share of extraction peaked in the late 2000s, when it provided upward of 95 percent of global REE [rare earth element] output; it now accounts for 55 percent. However, China accounts for about 80 to 90 percent of processing and separates nearly all heavy REEs; because of this dominance in the market, the processing sector

is where the risk of disruption is greatest.28 is the same sector that China leveraged when Japan was threatened with REO restrictions in 2010. In fact, nearly all rare earth ore mined in the United States (43,000 tons in 2021) is sent to China for separation and purification. This dominance resulted from China’s ambitious mining programs, an inability to enforce national policies that led to illegal mines, and a disregard for pollutants and by-products that create

environmental waste.

The Rand researcher goes into some detail about risks of disrupted supplies, but in broad terms, the policy steps here are fairly straightforward. (You will be stunned to know that the Rand researchers believe a “whole-of-government approach” may be needed here. Personally, I’m not holding my breath for the announcement of some policy problem that is said not to require a “whole-of-government” approach.) For the short-run, having stockpiles of rare earth elements that could last a few months may be useful.

For the longer run, the answers involve allowing expanded mining for these rare earth elements, as well as finding ways to substitute other more common minerals for some of their uses and to recycle already-mined supplies. It also requires building processing plants for these materials. Some of this, like searching for substitute materials, the private sector will eagerly do on its own in response to supply shortages and higher prices. But for other parts–like opening new mines and processing facilities–governments are going to have to strike a balance between environmental concerns and actually allowing a reasonable number of such projects to go ahead at a reasonable time and cost. That part of the challenge may be more political than economic.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest