Comments

- No comments found

There have been numerous studies on changes in the thalamus, due to Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s.

A recent study, “Physical and Mental Activity, Disease Susceptibility, and Risk of Dementia” assessed how daily habits and chores may reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

Another study, “Association Between Self-Reflection, Cognition, and Brain Health in Cognitively Unimpaired Older Adults” stated that 10 minutes of daily reflection could reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s.

The Alzheimer Society of Canada provided a recommendation list on how to challenge the brain to slow progression of dementia.

Another recent study, “Variation in Population Attributable Fraction of Dementia Associated With Potentially Modifiable Risk Factors by Race and Ethnicity in the US” stated that in the US, “the estimated proportion of the population with dementia that was associated with modifiable factors was 41.0%; this varied by race and ethnicity: 35.8% for Asian American, 45.6% for Black, 46.7% for Hispanic, and 39.4% White individuals. The factors with the greatest contributions were hypertension, obesity, and physical inactivity.” or simply, “40% of all-cause Dementia in the US is Preventable”.

A further study, “Motor Learning Selectively Strengthens Cortical and Striatal Synapses of Motor Engram Neurons” observed motor memory in the brain, and its differentiation from others. It mentioned the possibility that understanding it could be useful in finding causes of Parkinson’s disease.

Neurodegenerative diseases are generally described as those with losses to structure and function of neurons. There are several possible factors that could be responsible, but as observed in the above studies, lack of physical and cognitive activities are included.

But where in the brain do physical activities and cognitive inputs begin?

The starting point could be sought for limits, extents, cycles and so on, for neurodegenerative responsibility elsewhere.

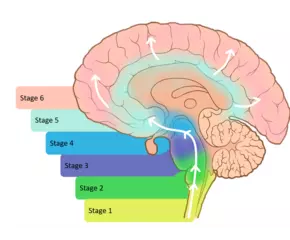

The thalamus is a major sensory and motor processing or relay hub in the brain.

All sensory inputs [except smell] arrive at the thalamus, before relay to the cerebral cortex.

Smell arrives at the olfactory bulb. A recent study, “Rapid olfactory decline during aging predicts dementia and GMV loss in AD brain regions” said that rapid loss of smell could predict dementia.

In early cases of Alzheimer’s, according to a research project, “Thalamic Control of Memory in Alzheimer's Disease” the thalamus is noted not to be affected.

But since the thalamus relays most external stimuli used for cognitive functions [including daily reflection, brain challenge, daily habit or chores] useful against the disease, could activities in the landing spot not be particularly decisive for what gets relayed elsewhere in the brain, for interpretation?

It can be theorized that sensory processing in the thalamus is into a uniform unit or a uniform quantity.

It can also be theorized that thalamic nuclei act as entry ports to motor and sensory functions coming into the brain.

These ports are varied based on function, parts, location and so on. Tastes, theoretically, can have a port of different intensities at different parts of the tongue, same for touch across the epidermis, same for ears and so on.

It can be postulated that the uniform quantity or unit of thalamic processing is thought or its form. It is what goes on to be used across the brain, or what becomes the representation of those functions, elsewhere across the brain.

Theoretically, thalamic ports shape thoughts [for priority, speed, structure, dimension, pairing, cycle and so on]. It is thought emergence and properties that determine how they do elsewhere.

It is possible that bad shaping or issues with supply of the forms of thought may lead to lower than usual intensity for parts of the brain, which may then lead to how some of the modifiable risk factors [obesity, hypertension, and physical inactivity] take root.

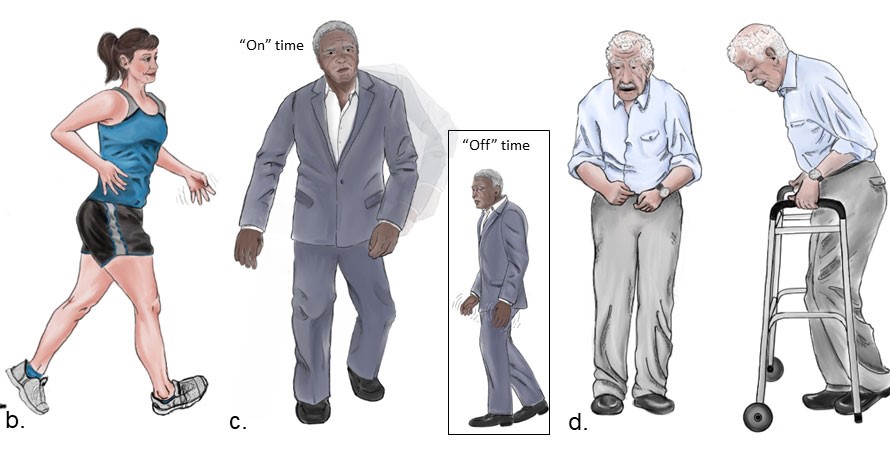

Theoretically, motor decisions are off the memory, or in memory locations. This means that knowing how to type a sentence, or write a note is something already grouped, given by the memory including how to control the hands.

However, as it gets done, feedback of what is being done gets integrated in the thalamus, to the memory to confirm, in a rapid cycle.

Expanding a thalamic model of thought properties and emergence could become another way to understand and design care against certain aspects of neurodegenerative diseases.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest