Comments

- No comments found

I want to begin with my conclusion to the question posed in the title.

There are several reasons for this. First, the conclusion directs the narrative that follows, and there is no need to keep the answer/conclusion a secret. This essay is not like a fictional novel where an ending that is shared in advance may ruin the story.¹ Second, in this time of the pandemic and its aftermath, our capacity to concentrate has waned and so it seemed wise to share the conclusion upfront in case readers wander off or start and stop reading periodically because they get distracted or there are other more pressing issues at hand in their home or work lives.² Third, the answer itself matters as it gives us hope and a reason to trudge onward, something that can benefit all of us as we manoeuvre in troubling times.³

Finding concrete positive approaches – ways of recognizing and dealing with trauma affecting students –opens this reality: some good can come from bad.⁴ And, that reality can provide us, too, with the courage to continue our work in the field of education. Here’s the answer and I state it declaratively: yes, trauma can improve education. The latter sentence, however, cannot stand alone; it needs to be accompanied by an “if.” The harder part of the answer is the “if,” and the ‘if” is what this essay addresses. It explains how, if we understand trauma and its symptomology and use trauma responsive strategies to address them, we can improve how our educational system operates from early childhood through adulthood. If we can name the extant trauma and recognize its symptomology, then we can tame it in ways that improve educational outcomes. And, if we frame the trauma – as in recognize its significance and omnipresence – we can surely change how our educational institutions operate on a day-to-day basis.⁵

Let’s start with this reality. As the one-year anniversary of the pandemic has just occurred in the U.S., many people have experienced and are experiencing trauma as a result, directly or indirectly, of COVID. While some may not use the term “trauma,” and instead prefer or use terms like “stress,” “anxiety,” “distress,” and “lack of wellbeing,” it is impossible to deny that our individual and collective lives have been upended. We may exhibit different trauma symptomology but these differences demonstrate trauma’s impact. And the impacts are not just on us as individuals; the impacts are on families, communities and workplaces⁶ and their respective functionality or, in many cases, dysfunction.⁷

We have experienced and continue to experience racial and ethnic discrimination and divides, with accompanying tensions and protests. This reality has changed and is changing our rhetoric and forms of engagement. We have witnessed political schisms that have divided families, communities, states and a nation and led to riots at the nation’s capital that resulted in death and injury. We have had contentious elections, including a presidential election that many still believe was “stolen” through election fraud. We have had massive natural disasters, including fires in California and water and electrical disruption in Texas. We’ve had immigration crises including the detention of minors in facilities that are not suited to provide them with adequate care.⁹

This essay is specifically focused on the impact of the pandemic-related traumas on education – from early childhood through adult education. The starting point, as noted earlier, is acknowledging and then understanding the traumas and accompanying symptomologies that have occurred within our educational system and the individuals and organizations affected. Then, we need to reflect on already deployed and to be deployed solutions for ameliorating the trauma symptomology. These solutions provide us with improved pathways toward positive change – if we can see them.

This essay rests on this truth, reinforced by science and research: trauma, once experienced, does not disappear. It shapes our memory, our cognition, our behavior, our feelings, our concentration, our engagement, our thoughts, and our physical wellbeing. True, it can be ameliorated in a myriad of ways, and we are learning more and more as research on trauma progresses.¹⁰ What these observations mean is that we will never return to the world as we knew it. We cannot go back; there is only one direction and that is forward (unless we stagnate). To use an analogy to wartime experiences: once one has lived through and fought a war, those memories and the impact of that wartime experience do not get eradicated even when the war ends and the soldiers return home. We need to stop asking this question: “When will we return to ‘normal?’” ¹¹

The emphasis on “returning to normal” is misguided and misstates the reality of how trauma operates within our brains and bodies. Even referencing a “new normal” suggests that order and regularity will reappear when schools reopen. Sadly, this isn’t an immediate process and in some cases, we will slip back to what was as if it was the paradigm of excellence. Trauma changes us, whether we are aware of those changes and whether the changes are recognized. Some of the alterations are within our brains – changes to our neural pathways, brain chemistry and brain biology. Neural mapping sheds insights into the way the brain responds to trauma. Specifically, trauma has an impact on identifiable parts of the brain (the amygdala is but one example), and most of those changes are not reversible. We can compensate for them; we can rebuild neural pathways; we can have brain workarounds due to the brain’s remarkable neuroplasticity. We can, in a very real sense, train our brains.¹²

To state the obvious, then, we are forced to find new approaches to navigating the changed minds and bodies of our students, whether we want to or not. This will take time. Here’s the good news: some of the new approaches are, in fact, better than how we taught and engaged with students pre-pandemic if we see new adjustments in a positive light, with a willingness to accept change and admit that what was is not always better than what could

That is challenging for those of us wed to the past and accustomed to certain approaches and patterns that have been with us (and have been successful at least in part) for decades. While we do not need to toss everything from the past out (baby with the bathwater problem), we need to reflect on how the pandemic has changed our students and our educators and how those changes could change education for the better.

This essay also explicitly recognizes that the traumas of the pandemic will not end when the pandemic recedes, vaccinations reach a high number and/or herd immunity occurs. It is not as if trauma and its symptoms are immediately shut off when the pandemic threat lessens. Getting rid of masks and eliminating social distancing will not feel instantaneously comfortable. We are not used to touch except within our bubble. In short, trauma isn’t a light switch that got turned on and can now get shut off at a set moment in time. Think about the absence of going to movies, museums, cultural and religious events; think about the lack of attendance at sporting events for those sports that are proceeding. July 4th, a date set by the president as a day to re-start our nation, will not be a cure-all day. All trauma symptomology will not evaporate with picnics and fireworks and festive music celebrating our nation.

There are many reasons for this. For starters, more than 590,000 individuals in the U.S. have died due to COVID; their deaths have lasting impacts on families, friends, workplaces and communities. Next, those who have spent a year or longer working from home and separated from family and friends will not suddenly and comfortably enter crowded places, commence extended travel by plane or train and engage through touch with others (handshakes and hugs may be a thing of the past). Workplaces will change and remote working, in whole or in part, will persist. Schools, shut and reopened all at once or in phases or stages or even haltingly, will not be the same. Students have changed; teachers/professors have changed. We can’t return to the status quo ante; that is fiction.Instead, we need to find a new reality.

Trauma from the pandemic has come from many sources resulting in different symptomology among individuals: death from COVID; getting ill and recovering (in varying degrees) from the effects of COVID; losing a loved one due to the pandemic, often without an opportunity to mourn in traditional ways, whether religious or cultural; disparate healthcare delivery and rates of death; declining employment with many industries shuttering their doors; loss of homes (whether rented or owned); lack of adequate food leading to growing food bank lines; schools and colleges closing and reopening in varying ways including online learning, hybrid learning, synchronous and asynchronous learning and in-person learning (often interrupted by short and longer-term closures); social distancing and masks (including debates as to their utility); disparate educational impacts and declining mental health of students of all ages and stages; fatigue of front line and other workers; being “Zoomed out” from too much online engagement; family dysfunction, evidenced in part by rising divorce rates and increased abuse of drugs and alcohol. The list of what has and is occurring is long and its effects run deep and wide.¹³

It is easy to feel discouraged. There are many reports of folks being “COVID-fatigued,” “COVID weary.” Exhausted. Tapped-out. Cooked. There’s a sense of “enough already” and could we just move forward. To add a touch of humor, I have done workshops where I have started with this question: If you are a potato, how do you want to be cooked? I have answered mashed. I have answered boiled. All answers reflect something about how I and others who answered feel.

But, the pressing question within the educational arena is how we can move forward and what approaches, actions, and activities (the three A’s) we can take to enable us to deal with the extant trauma symptomology in our students/educators and then adopt and adapt to changes within our schools/colleges related to the new state of our world.

For me, the starting point is a recognition that “hope” exists. And, critically, “hope” isn’t a passive verb, although some view it that way. Hope isn’t just sitting down and saying we want things to be better. Wishing isn’t the aim here. It isn’t about lamenting either. No, “hope” is an active verb that begs for us to act, to do, to be open to new ideas. Hope is what comes when we recognize the power of change and our capacity to implement that change. And, hope requires courage in the form of a fundamental belief that the risks accompanying change are not only worth it but a necessity.

Three added thoughts on hope. First, there is continuing research on trauma and approaches to remediating (not eliminating) it. These new approaches, grounded in brain science among other fields, offer promise. A recent book on microglia, The Angel and the Assassin, is but one example. New pharmacological interventions are being developed and tested. Positive childhood experiences and positive adult experiences offer ways to offset adverse childhood and adult experiences.¹⁴

Given the amount of trauma in existence, each of these developments offers hope to the millions of individuals struck by trauma over the past 12 – 18 months. Second, it is easy to forget to retain hope. In the face of adversity, it can slip away. That is why I always carry “hope with me in the form of a ceramic stone that I can rub between my thumb and my forefinger. It helps to realize, too, that the path forward isn’t straight. There are hurdles. There are steps backwards. Holding hope helps.

Third, we need to celebrate hope. It needs to be shared and communicated. It can be recognized in Houses of Worship and community organizations and educational institutions. It can be evidenced by politicians. It can be repeated by leaders. It can be cultivated. To paraphrase Barbara Kingsolver, "hope" isn’t something we just sit and admire. We need to engage with it; we need to live it.

Strategies currently deployed or that could be deployed can be categorized based on whether they are micro or macro in approach. Micro strategies are typically smaller in scale and may involve a single classroom with a specific teacher’s intervention. That said, multiple micro strategies can, as a collective, produce larger systemic change. There is, in essence, power in numbers.

Macro changes involve institutional culture and institutional messaging; these tend to be “top down” changes although they are enriched when their design and implementation has been achieved through the engagement of the many constituencies within school/college communities. Although macro changes do not require “buy-in,” their stickiness (enduring change) is suspect unless there is broad-based agreement.

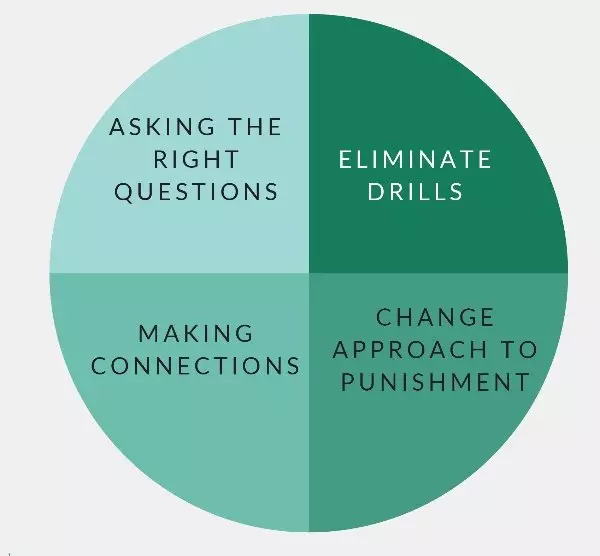

Indeed, we need both micro and macro change, working simultaneously. If we have one without the other, we are still making improvements. But, in a sense, our overall effectiveness hinges on working from the bottom up and the top down at the same time.¹⁵ In describing four categories of strategies here that have both micro and macro components within them, specificity is provided so readers can literally try what is described here. All of the proffered strategies have been tested within our educational system and they are born from experiences in the trenches. As with all suggestions given a contextually, they need to be adapted to particular institutions, cultures and contexts.

They also can be adapted to different age groups and different settings.The latter two observations speak to the importance of personalization of the suggestions so they meet the needs of the students and educators being served. I suspect that some of the four categories of suggestions identified here will sound familiar because they have been tried by educators and institutions without any trauma nomenclature. They have been adopted as quality educational practices without a specific link to trauma and perhaps with a focus on social-emotional learning. While there is no specific need for labeling something as stemming from trauma, there are two positive points that derive from such labeling.

First, labeling recognizes the presence of trauma; it names it and frames it. And, if you can name it, you can tame it. Second, trauma-responsive strategies are like a rising tide: they lift all boats. While aimed to assist those who are traumatized, the suggested strategies improve educational outcomes for all students. We can, then, consider these suggestions win-win for all students and educators. One added note: these are not the only possible strategies for generating hope. However, they are for me among the most powerful and persuasive strategies.

If we put on a trauma lens through which to think about education, then we will be asking different questions of ourselves as educators and of our students.¹⁶ The easiest way to picture the impact of this shift in focus is to look at the books titled Poemotion by Takahiro Kurashima.¹⁷ Each book contains illustrations that are then viewed with a piece of plastic. This plastic page animates the illustration, allowing you to see something that you did not perceive before. Initially, it is surprising, perhaps shocking, to see what the trauma lens adds to existing landscapes. Consider the questions one might ask of students if educators are not wearing a trauma lens. Here are typical non-trauma focused inquiries: “Why are you acting badly?” “Why are you not paying attention?” “What happened to the excellent student who was here prepandemic?” “Why didn’t you keep up with the assignments online?” “Why can’t you sit still?” “Why are you still so still and alone?”

With a trauma lens, we focus on what has happened to students and what happened is, in the context of trauma, not of their own making. For example, consider replacement questions/queries that recognize the “something happened” scenario: “Share how you navigated during the pandemic.” “Share what was hardest for you.” “Describe a positive and negative feeling you have being back in school/college in person.” “What can I do to help you?”

Call these latter questions “door openers,” allowing students to express themselves. To be sure, the same questions could be asked of educators by administrators. These, too, would

open the door to different kinds of non-judgmental conversations. There’s another value in this shift in questioning: we begin to determine who our students actually are. We often try to teach the students we were ourselves; or, we make assumptions about students and their behavior and academic performance; or we want better students and lament the students we have. None of these options enables us to teach the students before us in a class. We need to understand who they are if we are to teach them well.

I can hear the hue and cry already: that is not our job. Our job is to teach and as long as we teach the required material, we are doing our job. No, actually. The goal of educators is to enable and facilitate student success. In the absence of understanding who our students are and how they learn and what needs they have that are impacting their educational success or lack thereof, we are failing them.¹⁸

The post-pandemic approach suggested here works by improving our understanding of our students are now and as such, is likely to produce more effective student outcomes both academically and psychosocially. We know that if students feel someone cares about them genuinely and believes in them and their success, these students are more likely to succeed. At the end of that day, that is what we want for all students: opportunities for them to become their best selves. Here’s the bottom line: Wearing a trauma lens allows for a different set of insights and questions and opens the door to forward movement recognizing that all individuals involved in education have changed due to the trauma of the pandemic. The very fact that these questions don’t place blame but recognize the “this is what happened to me” realization will impact how students can develop and reengage.

Our brains are wired for connections and one of the prime effects of trauma is to truncate these connections. Students can become dysregulated or disassociated or overregulated, all and each of which curbs quality engagement with adult educators and peers. We know too that a quality relationship with one or more non-parental adults is critical for student success and has been deemed a “positive childhood experience” that can be viewed as an “offset” to adverse childhood experiences.¹⁹

We know too that masks and social distancing have curbed connections. We keep our expressions largely to ourselves and we remain far enough apart that we cannot touch or hug or shake hands or get a pat on the shoulder when the going gets tough. For many younger children in schools, they need more than physical activity; they need to learn to read cues; they need to feel supported through physical signals and facial expressions; they benefit from a hug or a pat on the back.²⁰

I remember one of my son’s teachers at a well-known NY private school who started the school year by saying “I don’t do tissues,” by which she meant she was not there to wipe away tears or deal with runny noses. For me, that comment was emblematic of her approach to teaching and her students. And, in one of those helicopter moments as a parent (who was also an educator which added to my credibility), I had my son removed from her class that very day. Another teacher who gave him an F on a perfect math homework assignment because he didn’t staple the paper on the top right (yes, right) didn’t fare too well either. Neither did the teacher whose questions were drawn from Cliff Notes (which my son noticed as he too was using that “resource).”

Positive connections can take many forms – dialogue, touch, visual cues, regular communications and shared activities. The more the merrier in a sense. If adults can augment student communication, then they will be working toward restoring the connectivity that has been truncated by the pandemic. Consider these strategies for facilitating educator engagement with students. It is not enough to learn students’ names, although that is a key starting point. It means using that student’s name when that student does something positive that is worthy of recognition. For example: As Julio observed yesterday... Or as Sara mentioned in her paper.. Or as Noah raised in class today...

Then, educators can communicate with students through how they grade their papers and share feedback. Out go the red pens or redlining (done in red). In comes both positive and negative feedback. The comments by the educators need to ask questions or share observations and link comments to things the student has learned in class or shared in other work submitted. And, as a rule of thumb, we need three positives for every negative comment, scaffolding criticism so that students learn that all work – even “A” work – can be improved.

I can anticipate the criticism of this suggestion too. Isn’t this coddling and creating fake praise? The simple answer is no. Helping students learn is NOT coddling. And, there certainly have to be some positives to a student’s work – at a minimum, they tried and turned something in. That already is a positive. There is the old adage, “we don’t get rewarded for effort,” but that phrase is misguided in the context of trauma. For traumatized students who are struggling to engage, any encouragement is beneficial. And, if we don’t exert effort, then for sure we can’t get to excellence. True, effort isn’t enough but its presence is a prerequisite to educational growth.²¹

Consider educators who during the pandemic found new ways to engage with students (and for younger children, their families). Some used email. Some mailed (as in USPS mail). Some

visited outside student homes. Some dropped off materials that students needed because they couldn’t get to a pick-up spot. Ask whether these approaches need to be eliminated when students appear in person. Surely, we can augment what we did before with what has worked and been effective during the pandemic. Bottom line: The more personalized contact and connection, the better.

Pre-pandemic, we had fire drills. We had live shooter drills. We had earthquake drills. These were often unannounced. And, when they occurred, learning in a classroom was interrupted. And, when students returned or re-engaged, the “drill” was often not debriefed. We just assumed that students navigated its meaning and returned from the event ready, willing and able to learn. Parents and guardians oft-time supported these disaster preparations as key ways of protecting their children from possible harm.²² But, the effectiveness of these drills is not universally supported by the data. Fire drills do not necessarily make evacuations better in the event of a real fire.

Live shooter drills, some of which involve rubber bullets and mock victims with fake blood, scare many children. They start envisioning violence in their schools and what should be a safe place feels

unsafe, especially when the drill is not announced and described in advance and debriefed at the end. Indeed, an entire industry has grown since school shootings became more prevalent and they have created a sense of “need;” if schools don’t prepare, their students will die.²³

Preparation for prospective disasters can take many forms. Active shooter drills could be replaced by thoughtful, contextualized conversation and discussions. Students could offer strategies and suggestions. Those who are particularly triggered by these conversations could be permitted to go elsewhere during these discussions and an educator could engage with them in privacy. Imagine the child who lost a parent to gunfire or a family home to fire or flood sitting through a discussion of how to avoid a disaster. The idea of drills in the post-pandemic era takes on added negative meaning. We have spent the better part of 12 months being in a disaster. And, the efforts to mitigate its effects, particularly on low-income minority communities, have not been met with success.

People have lost loved ones and have been separated from peers. Traditions that governed how to mourn and how to celebrate have been upended. In addition to curbing drills, ponder the sound of the bells and buzzers that dominate schools. They were startling for some pre-Pandemic. If one is already on edge with one’s autonomic nervous system on high alert upon return to schools, these sounds are the anthesis of soothing. Why can’t we substitute harsh sounds with pleasant sounds? Bells? Chimes? Tones that start softly.

These two approaches – drills and deafening buzzers – are not the only traditions within schools that could change based on the trauma students and educators have experienced in the past year. If we pause long enough to reflect on how we conducted education in the past, we can look specifically for entry points to enable change.²⁴

Consider these possibilities: a greeting committee when students enter school each day; changed materials on the walls and in the halls and stairwells (why are stairwells often gray with no art or colorful paintings?), opportunities for students to express themselves on walls with post-its or chalking on floors where tiles are replaced with chalkboards. And, for those teaching the early grades, eliminate games like musical chairs unless the leftout students are given another task or role that makes them feel welcomed, not eliminated.

Consider how during the pandemic, “misbehaving” children could not be asked to leave the classroom and go to the principal’s office. Also, if students did not show up online (a common event), we did not immediately notify the truancy officers and start punishment procedures. And, there were students who were online but were not actually there (literally or psychologically), and we certainly did not report these students as truants. When students acted badly online, we oft-times (with younger children) reached out to their parents for some form of remediation.²⁵ And, this is the key part: educators often tried on their own to deal with their students.

That approach – helping children navigate their behavior in place without leaving the room – is a worthy approach if we can add needed supports. Indeed, moving forward, we should consider the idea of bringing some professional into the classroom rather than banishing a student from the classroom.²⁶

This handling situations “in place” has many benefits.²⁷ First, when traumatized students are acting out, the last thing they need is disconnection. Indeed, that is what they are already experiencing from trauma, which is why they are behaving as they are. Instead, consider the concept of processing in place where a teacher can address what is occurring, taking some moments alone with the student who is struggling, or asking for another trained educator or administrator to come into the classroom to provide assistance to the struggling student.

One of the benefits of this approach is that it showcases to other students in the room how difficulties can be navigated; rather than punishment, there are approaches to enable the student to stabilize and return to the learning environment. Moreover, the approach isn’t punitive; it is rehabilitative. Finally, processing in place recognizes that absence isn’t an answer; presence is.

In terms of student attendance, we currently have a huge problem as many students have tuned out – literally and figuratively. The approach to dealing with this is not suspension; indeed, the “distant” students need the opposite of banishment. They need to be welcomed back into the fold and helped to believe that they can succeed within the school environment.²⁸

Moreover, if we are to begin to close the equity gap,²⁹ we need to get students who might want to leave school (including to help their families through work or caregiving) to see the value of obtaining an education. That doesn’t come from a punitive stance; instead it comes from making school a place that is safe, stable, secure and sustaining. School can become a place where students with troubled home lives go, if we recognize their needs and help students find their way into the school building. Something positive has to be there for them if we get them through the door, especially if parents themselves disliked the education they had.³⁰

One insight many teachers have gained during the pandemic is a sense of the homelife of students. They have seen them signing onto their computers; they have seen parents and other siblings and family in the background; they have heard background noise; they have watched parent-child interaction if the child is not paying attention or is succeeding. In short, teachers are seeing what they often did not see before: context and family functionality.

That contextualization, augmented when there has been home delivery of supplies or academic assistance (both of which have thankfully occurred for at least some students), has enabled teachers to learn more about who their students are in real life, in real-time. The insights have often allowed teachers a glimpse as to why students are struggling. I remember one teacher expressing how she had to tell a parent to please wear more clothing online. As the teacher explained, “I dress for teaching and you and your child need to dress for school.” The absence of respect for education and the presence of overt sensuality needed to be curbed.

Taking contextualization and new approaches to misbehavior into the educational arena, we will improve opportunities for students to become their best selves. To return to the Introduction, we can now answer the question of whether trauma can improve education with a one-word answer: yes. And, this essay has identified some key solutions to enable us to get to “yes” (to play off the title of a book with a similar phrase).³¹

But, we are left with the “how” questions. How do we make more educators (among others) aware of trauma and its symptomology and modes of amelioration? How do we move trauma and its remediation from the outskirts of conversation to the center, although to be sure, some schools and school systems are already moving or have moved in this direction? Just look at the Trauma Sensitive School Movement by way of example. I hope this essay, which is linked to a podcast and lecture event at the Proctor Institute at the Rutgers Graduate School of Education,³² can be seen as a type of map.

So far, it has four destinations evidenced by the four identified categories and the list is surely not complete. Call this essay an effort at educational cartography. With the map in hand, we can start a journey. It is a journey we need to begin now – for the benefit of all of our students. We can go to the four identified destinations (the four categories developed above), and we can add destinations by filling out the map from experiences during and after the height of the pandemic. And this matters: we can carry our maps with hope – because we have a pathway forward…. if we just begin to walk in that direction. Trauma abounds; so do solutions.

Karen Gross is an author and educator as well as an advisor to non-profit schools, organizations, and governments. Her work focuses on student success with a specialization in trauma. She has worked with institutions planning for and dealing with person and nature-made disasters including shootings, suicides, immigration detention, family dysfunction, hurricanes and floods. Recently, her work has focused on the impact of the pandemic on student learning and psychosocial development.

1. For an interesting take on whether surprise endings actually help a story, see: https://www.universityofcalifornia.edu/news/spoiler-alert-spoilers-make-you-enjoystories-more. By Andy Murdock, “Spoiler Alert: Spoilers Make You Enjoy Stories More (May 24, 2016).

2. https://theconversation.com/having-trouble-concentrating-during-the-coronaviruspandemic-neuroscience-explains-why-139185 by Beatrice Pudelko, “Having Trouble Concentrating During the Coronavirus Pandemic? Neuroscience Explains Why.” The Conversation June 8, 2020.

3. https://syd.iamyiam.com/en/blog/importance-of-hope-during-the-pandemic/ “The Importance of Hope During the Pandemic,” Dec. 3, 20202. See also: Karen Gross “Trauma Tools as Schools Stagger Forward,” https://medium.com/age-of-awareness/trauma-toolsas- schools-stagger-forward-e9836001d580 August 2020.

4. Tongue Twisters and Beyond: Words at Play by Karen Gross (Shires Press 2020). Now available at Amazon and www.northshire.com and at: https://sellfy.com/karen-grosseducation/p/tongue-twisters-and-beyond-words-at-play-book/ (downloadable PDF)

www.karengrosseducation.com/thefeelingalphabet/ (downloadable PFD from website

www.karengrosseducation.com)(with Dr. Ed Wang)

www.karengrosseducation.com/trauma-toolbox-a-how-to-guide/ (downloadable PDF from website)

https://medium.com/age-of-awareness/playmobil-workplaces-and-traumaae86241a1079

https://medium.com/age-of-awareness/missing-pieces-and-filling-holes-findingsolutions-to-enable-student-success-a31f0475592d

5. A more detailed description of this architecture – name, tame and frame – appears in Karen Gross, Trauma Doesn’t Stop at the School Door: Strategies and Solutions for Educators, PreK-College (Teachers College Press June 2020) (hereafter, Trauma Doesn’t Stop.”

6. For a clever and insightful piece on how workplaces have changed, see: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/office-detox-anyone-overcoming-year-406-billion-extrageorge-anders/trackingId=YlFoghpDYKKw9zu0UpKC2A%3D%3D By George Anders, LinkedIn, March 2020.]

7. https://nyulangone.org/news/trauma-children-during-covid-19-pandemic Adam D. Brown, “Trauma in Children During the Covid-19 Pandemic;” https://www.healthline.com/health-news/the-world-is-experiencing-mass-trauma-fromcovid-19-what-you-can-do by Leah Campbell, “The World is Experiencing Mass Trauma from Covid-19: What Can You Do? Sept. 8, 2020.

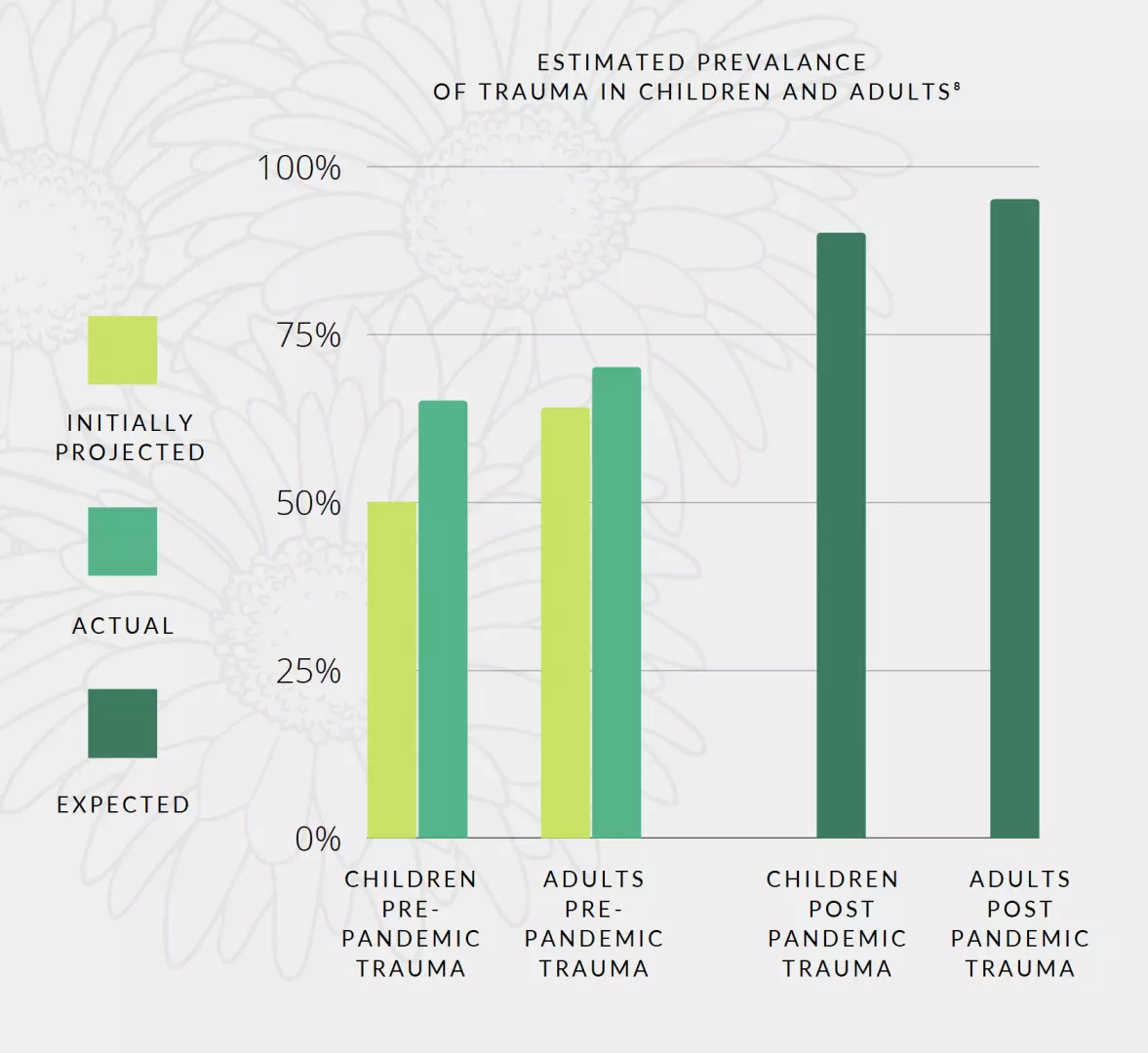

8. https://www.cahmi.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/aces_fact_sheet.pdf

https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/articles-and-news/2017/10/traumatic-experienceswidespread-among-u-s--youth--new-data-show.html

https://resiliencycollaborative.org/aces

http://recognizetrauma.org/statistics.php

https://www.healthline.com/health-news/the-world-is-experiencing-mass-trauma-fromcovid-19-what-you-can-do#Understanding-the-definition-of-trauma

Taxman, Owen & Essig, 2021

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0240146

https://apsa.org/PTSE

https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/report/kff-health-tracking-poll-july-2020/

https://dana.org/article/pandemic-brain-parsing-the-mental-health-toll/?gclid=CjwKCAjwgZuDBhBTEiwAXNofRKXlcG5GQOWDxF_FZ_DYbDmLfa3Ue_v01GcSgwxyeDSo2Lmf2FehlBoC5-YQAvD_BwE

https://www.samhsa.gov/child-trauma/understanding-child-trauma

https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Traumainfographic.pdf?daf=375ateTbd56#:~:text=70%25%20of%20adults%20in%20the%20U.S.%20have%20,experience%20%20Post%20Traumatic%20Stress%20Disorder%2C%20a%20very

9. See e.g. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7139255/ by Wei Shi and Brian J. Hall, “What Can We Do for People Exposed to Multiple Traumatic Events During

the Corona Virus Pandemic?” April 8, 2020; https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09515070.2020.1766420 by Emily M. Lund, “Even more to handle: Additional sources of stress and trauma for clients from marginalized racial and ethnic groups in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic May 2020; https://hechingerreport.org/opinion-for-our-many-black-and-brown-childrenthe-threats-to-their-physical-safety-now-and-into-the-future-are-eating-away-at-theirinsides/ by Karen Gross, “OPINION: ‘For our Many Black and Brown Children, the Threats to their Physical Safety now and into the Future are Eating Away at their Insides’” June 2020; https://karengrossedu.medium.com/dont-we-have-enough-trauma-e6a67b92bc40, by Karen Gross, “Don’t We Have Enough Trauma?” May 2020;

https://www.mhanational.org/racial-trauma;

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/racial-trauma#symptoms

10. See e.g. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/media-spotlight/201305/whenthe-trauma-doesnt-end by Romeo Vitelli, “When Trauma Doesn’t End,” May 2013; https://www.pchtreatment.com/does-ptsd-ever-go-away/ By Seth Kadish, “Does PTSD

Ever Go Away,” Sept. 2019; https://www.tcpress.com/blog/trauma-toolboxes/ by Karen Gross, “We All Need Trauma Toolboxes,” June 2020;

https://psychiatry.ucsf.edu/copingresources/covid19 “Emotional Well-Being and Coping

During COVID-19 “Emotional Well-Being and Coping During COVID-19.”

11. https://www.gwendolynvansant.com/home/2020/5/17/bouncing-forward-notbouncing-back-adapting-with-resilience by Gwendolyn VanSant “Bouncing Forward, not Bouncing Back: Adapting with Resilience” May, 2020; Karen Gross, Breakaway Learners (TCPress 2017). See also: https://www.technologyreview.com/2020/03/17/905264/coronavirus-pandemic-socialdistancing-18-months/ by Gideon Lichfield, “We’re Not Going Back to Normal,” March 2020.

12. See e.g. https://www.hcams.net/hcams-blog/how-trauma-affects-the-brain-a-primer “How Trauma Affects the Brain: An Overview,” June 2020; Karen Gross, Trauma Doesn’t Stop at the School Door, supra.

https://sdlab.fas.harvard.edu/files/sdlab/files/trauma_and_the_brain_1.pdf. See also:

https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/51343893.pdf by Sara McLean June 2016.

13. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/trauma#definition by Jayne Leonard June 2020; https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/9545-post-traumatic-stress-disorderptsd; https://karengrosseducation.com/trauma-and-adult-learners/ by Karen Gross Dec.2019 (CAEL).

14. The Angel and the Assassin :The Tiny Brain Cell that Changed the Course of Medicine (Random House/Ballantine 1/21/2020)by Donna Jackson Nakazawa;

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/fullarticle/2749336 by Christina Bethell et al Sept. 2019“Positive Childhood Experiences and Adult Mental and Relational Health in a

Statewide Sample;” https://lindsaybraman.com/positive-childhood-experiences-aces/, by Lindsay Brayman March 2021;

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2020/01/200113165057.htm, January 2020;

https://ct.counseling.org/2016/06/polyvagal-theory-practice/ by Dee Wagner June 2016;

https://adf.org.au/insights/mdma-ptsd/ June 2020; https://www.psycom.net/emdr-therapyanxiety-panic-ptsd-trauma/ By John Riddle, “EMDR Therapy for Anxiety, Panic, PTSD and

Trauma;” https://theimagineproject.org/eft-tapping/?gclid=CjwKCAjw3pWDBhB3EiwAV1c5rLtcojxWyvSgC8HL9vc3_9N59mF4q1P8iBGijtSIUwIzhMX8Q0nQhoC-rwQAvD_BwE

15. Trauma Doesn’t Stop at the School Door, Chapters 9 and 10, supra.

16.For a book identify key questions to ask of students and ourselves, albeit not tied to trauma, see James Ryan, Wait What? Harper One 2017.

17. Poemotion 1, 2 and 3, Lars Muller Publisher, 2013 (2), 2015 (1) and 2016 (3).

18. For the literature on the coddling and snowflaking of students and why some believe it is debilitating not helpful, see: The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad

Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure, by Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt (Penguin, Aug. 2019); https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-4824866/How-did-today-s-studentsturn-

snowflakes.html Dominic Sandbrook August 2017; https://quillette.com/2019/12/01/when-disruptive-students-are-coddled-the-whole-classsuffers/by Max Eden Dec. 2019;

19. Karen Gross, Trauma Doesn’t Stop at the School Door, supra Chapters 3 and 4. C A N T R A U M PAGE 2 0 A IMP ROVE EDUCAT ION?

20. “Commentary: Physiological and Psychological Impact of Face Mask Usage during the COVID-19 Pandemic” by Jennifer Scheid et al Sept. 2020

21. https://academeblog.org/2018/12/28/the-myth-of-the-campus-coddle-crisis-thecoddling-of-the-american-mind/ by John K. Wilson (Dec. 2018); https://eab.com/insights/blogs/student-success/why-texting-your-students-isnt-coddling/ Annie Yi (2016); https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/understanding-microaggressions-seeinginvisible-karen-gross/?published=t Karen Gross (2015); For an interesting take on the coddling conversation, see: https://ir.stthomas.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1430&context=ustlj by Rob Kahn,The Anti-Coddling Narrative and Campus Speech, 15 U. St. Thomas L.J. 1 (2018).

22. There is recognition that drills done well are not psychologically damaging. https://www.nasponline.org/resources-and-publications/resources-and-podcasts/schoolclimate-safety-and-crisis/systems-level-prevention/conducting-crisis-exercises-and-drills

23. For the risks of drills, see: https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2018/02/effects-of-active-shooter/554150/ by James Hamblin 2018; https://pdxparent.com/the-mental-impact-of-school-lockdowndrills/; https://www.fatherly.com/health-science/active-shooter-drills-traumatize-kidssafety/ by Joshua A. Krisch (Sept. 2020); https://districtadministration.com/active-shooterdrills-gun-violence-cause-trauma-school-safety/ by Matt Zalaznick February 21, 2020.

24. https://davidwees.com/content/school-bells-interfere-learning/ Jan. 2011; https://www.debate.org/opinions/should-all-schools-have-bells?_escaped_fragment_=&_escaped_fragment_=

25. https://edsource.org/2020/how-school-discipline-and-student-misbehavior-haschanged- during-the-pandemic/643758

26. https://edupstairs.org/sending-your-learners-to-the-principals-office-will-weakenyour- ability-to-manage-your-class/

27. https://www.naeyc.org/resources/pubs/yc/may2015/trauma-sensitive-classrooms;

https://www.med.unc.edu/ahs/ocsci/nc-school-based-ot/wpcontent/uploads/sites/765/2018/06/IntegratingTherapy.pdf

https://llatherapy.org/push-in-therapy-how-to-make-it-work-as-told-by-lla-therapists/

28. https://www.fox16.com/news/arkansas-schools-regularly-suspend-truant-kids-despiteban/;

https://www.lawyers.com/legal-info/research/education-law/absenteeism-andtruancy-the-cost-of-cutting-class.htm

29. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-and-social-sector/our-insights/covid-19-and-learning-loss-disparities-grow-and-students-need-help#;

https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2020/06/17/pandemic-has-worsened-equity-gapshigher- education-and-work

30. Schools can be places for healing trauma if we focus on that end-goal. See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6ZFpMISPQAo.; Creating Healing School Communities (School-Based Interventions for Students Exposed to Trauma) Paperback – August 1, 2019 by Catherine DeCarlo Santiago ; https://www.crisisprevention.com/Blog/Trauma-Informed-Schools

31. Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In May 3, 2011 by Roger Fisher (Penguin)

32. Trauma is an Invisible Backpack: How that Backpack Affects Students, Educators and Communities. Rutgers GSE. (2021). https://proctor.gse.rutgers.edu/traumaevent.

A version of this article first appeared in the Rutgers Graduate School of Education (GSE)

Karen is an educator and an author. Prior to becoming a college president, she was a tenured law professor for two plus decades. Her academic areas of expertise include trauma, toxic stress, consumer finance, overindebtedness and asset building in low income communities. She currently serves as Senior Counsel at Finn Partners Company. From 2011 to 2013, She served (part and full time) as Senior Policy Advisor to the US Department of Education in Washington, DC. She was the Department's representative on the interagency task force charged with redesigning the transition assistance program for returning service members and their families. From 2006 to 2014, she was President of Southern Vermont College, a small, private, affordable, four-year college located in Bennington, VT. In Spring 2016, she was a visiting faculty member at Bennington College in VT. She also teaches part-time st Molly Stark Elementary School, also in Vt. She is also an Affiliate of the Penn Center for MSIs. She is the author of adult and children’s books, the most recent of which are titled Breakaway Learners (adult) and Lucy’s Dragon Quest. Karen holds a bachelor degree in English and Spanish from Smith College and Juris Doctor degree (JD) in Law from Temple University - James E. Beasley School of Law.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest