Comments

- No comments found

It is a common belief, applicable across many different kinds of markets, that if you could just “cut out the middleman” and “pass the savings along to consumers,” everyone would be better off. Pharmacy benefit managers are quintessential middlemen.

Thus, when it comes to addressing high drug prices, going after them has considerable political appeal. Matthew Fiedler, Loren Adler, and Richard G. Frank offer some useful background in “A Brief Look at Key Debates About Pharmacy Benefit Managers” (Brookings Institution, September 7, 2023).

What do pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) do? The authors put it this way:

A PBM is an entity that administers a health insurance plan’s prescription drug benefit. One core function of a PBM is to negotiate drug prices with manufacturers; when negotiating prices, a PBM generally offers a drug a place on the plan’s “formulary” (which specifies which drugs the plan covers and on what terms and, thus, determines how much enrollees use the drug) in exchange for below the manufacturer’s “list price.” PBMs also negotiate with pharmacies, generally offering the pharmacy a place in the plan’s network (which increases how many of the plan’s enrollees use the pharmacy) in exchange for accepting specified prices to dispense drugs. PBMs perform administrative functions, notably processing pharmacy claims. Most of these functions (e.g., setting coverage terms, negotiating prices, establishing networks, and processing claims) parallel functions that insurers perform for non-drug benefits, but PBMs’ specialized knowledge of drug markets may allow them to perform them more effectively.

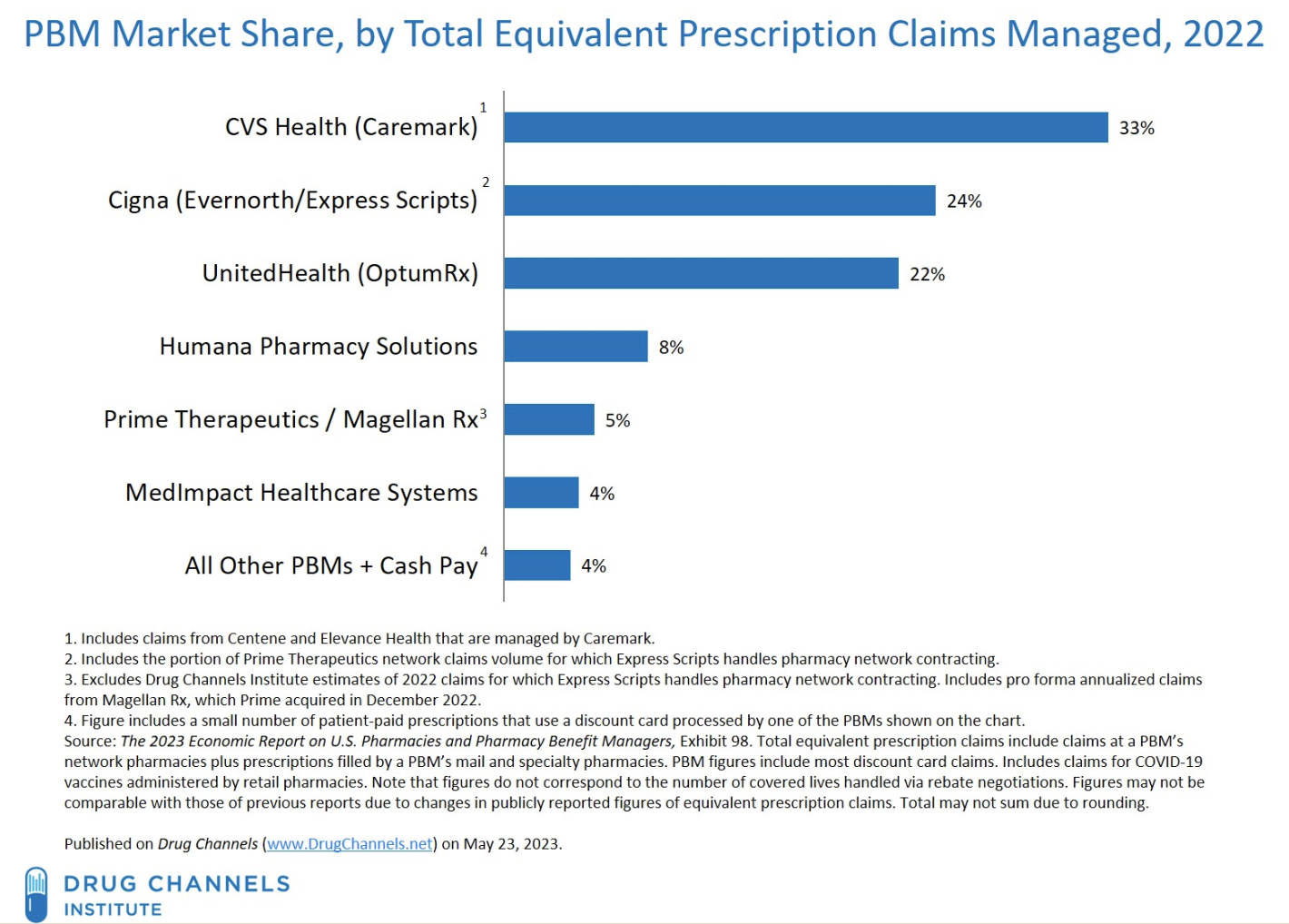

Who are the main PBM companies? Here’s a list. Note that about 75-80% of all claims are handled by three companies.

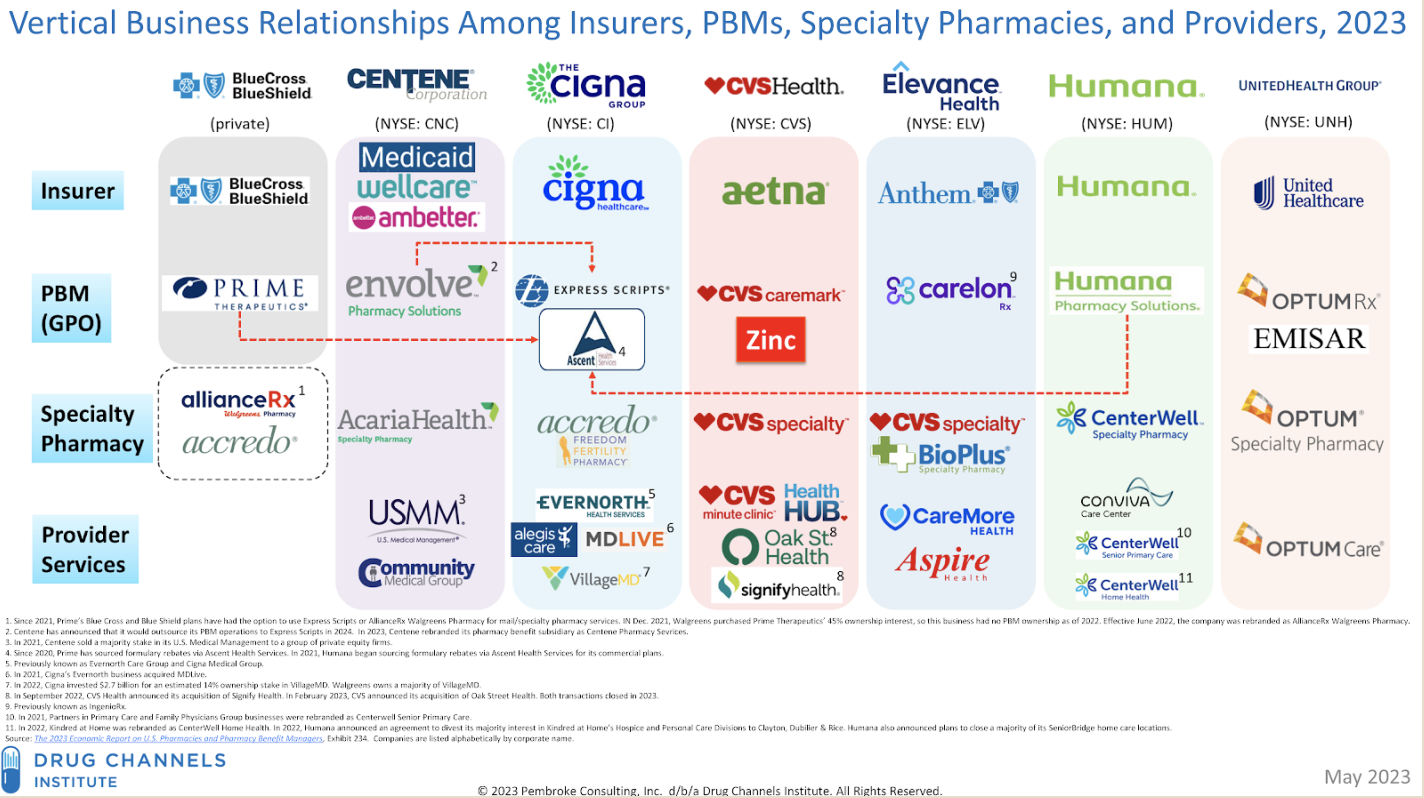

The list probably oversimplifies the role of PBMs. As the Brookings authors note, the PBMs are typically integrated with major health insurance companies. Here’s a chart showing major health insurance companies across the top, and who they use as PBMs for various purposes below.

What are the specific complaints against PBMs? Given that the big three control a huge share of the market, there is concern that the lack of competition might give them power to raise prices. Some concerns are more detailed. “The prices that PBMs charge payers for pharmacy claims often differ from the prices that PBMs pay the pharmacies that fulfill those claims,” so there is a “spread” that might be reduced. Sometimes, the rules that require patients to share costs for a certain drug are calculated in a way that is based on the original price of the drug, not on the discounted price negotiated by the PBM. When there is a manufacturer rebate for use of a certain drug, this money can sometimes flow to the PBM, rather than directly to patients. Overall, the notion is to find a way to squeeze these middlemen, and get lower drug prices for consumers as a result.

In their essay, it seems to me that Fiedler, Adler, and Frank are managing expectations about how much this approach is likely to achieve. For example, they point out: “Pre-tax operating margins for the three largest PBMs averaged a bit more than 4% of their revenues in 2022. Since PBMs’ revenues encompass both the

administrative fees charged to PBMs and payers’ net payments for claims, this implies that even completely eliminating PBMs’ margins would only modestly reduce payers’ drug-related costs.”

The potential cost savings from some of the steps being discussed are uncertain. For example, if you favor more competition among a larger number of PBMs, it’s important to recognize that a bigger PBM has more negotiating leverage. If you are in favor of the US government using its considerable financial clout to negotiate lower drug prices for Medicare and Medicaid patients, you understand the principle that a small-scale PBM will have less leverage when negotiating with pharmaceutical producers and with pharmacies than a larger one. It turns out that PBMs on average retain about 9% of rebates from manufacturers, so reducing this to zero percent will not have much effect on final prices.

As in most economic discussions about the role of middlemen, it’s important to remember that they (usually) don’t just sit around with their hands out, collecting money. Some entities need to negotiate on behalf of health insurance companies with drug manufacturers and pharmacies. Some entities need to process insurance claims for drug prices. I do not mean to defend the relatively high drug prices paid by American consumers compared to international markets, nor to defend the costs and requirements for developing new drugs, nor to defend some of the mechanisms used by drug companies to keep prices high. But while it might be possible to squeeze some money out of PBMs for slightly lower drug prices, and it’s certainly possible to mess up PBMs in a way that leads to higher drug prices, it doesn’t seem plausible that reform of PBMs is going to be a powerful lever for reducing drug prices.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest