The US dollar is sometimes called the world's "reserve currency," which is true enough, but doesn't actually capture the multiple ways in which firms and nations around the world make use of the US dollar. Moreover, these other issues can complicate how other nations are affected by changes in the foreign exchange value of the US dollar. Fernando Eguren Martin, Mayukh Mukhopadhyay and Carlos van Hombeeck lay out these issues in "The global role of the US dollar and its consequences," published in the Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin (2017, Q4).

Movements in the foreign exchange value of the US dollar of course affect US imports and exports: specifically, a stronger US dollar tends to boost imports (a stronger US dollar buys relatively more) and to weaken exports (a stronger US dollar pushes up relative costs of US producers). But changes in US dollar exchange rates percolate through the world economy in a number of other ways, too.

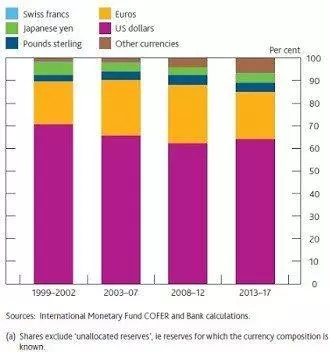

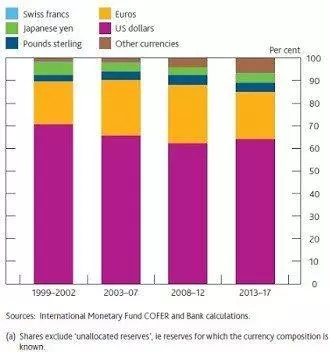

For example, central banks around the world hold "official" currency reserves, and they are mostly in US dollars.

Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (a)

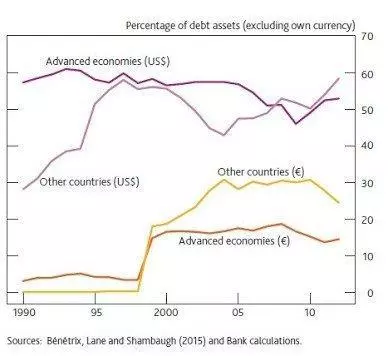

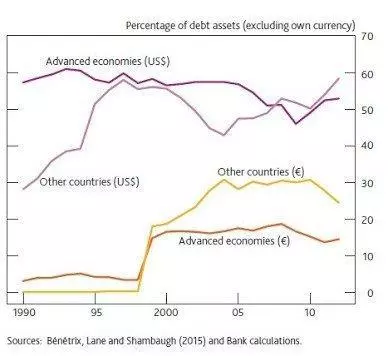

Most international borrowing also happens in US dollars, which means that those in other countries need to repay that borrowing in US dollars, which runs a risk of being difficult if there is a shift in US dollar exchange rates. For example, here's a figure of total currency debt not in a nation's home currency. Although euro-denominated debt has made a surge, my suspicion is that it largely replaced previous debt that had been in German marks, French francs, and the like. The share of US dollar-denominated debt is about the same as it was in the mid-1990s.

Share of Non-Home Currency External Debt Assets in US Dollar and Euros (a)

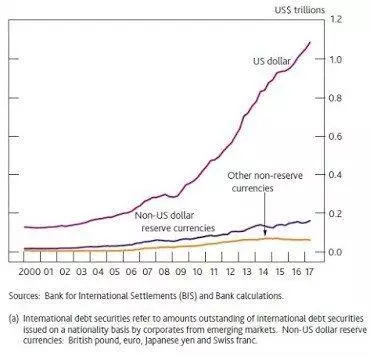

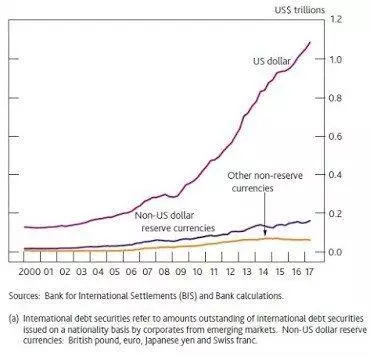

Similarly, when firms in emerging markets issue debt, they are most likely to do so in US dollars.

Debt Securities Issued in International Markets by Corporates from Emerging Markets (a)

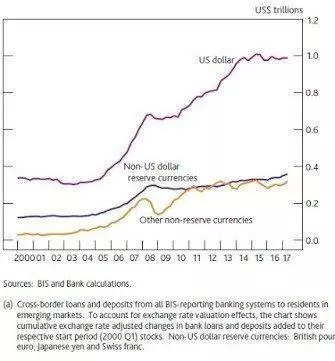

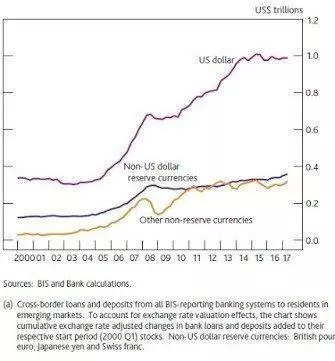

International bank lending to the non-bank sector in emerging markets is also mainly done in US dollars.

International Bank Lending - to Emerging Markets, Non-Bank Sector (a)

Finally, lots of international trade is invoiced in US dollars, even if the actual trade doesn't involve the US economy. This matters because prices of exports and imports are often slow to adjust to exchange rate movements. As the authors write:

"[There is an additional dimension to be considered given the large amount of US dollar-invoiced trade between non-US countries. Changes in the value of the US dollar could have different effects on countries depending on their shares of US dollar-invoiced exports and imports. Export and import prices are often slow to change in their currency of invoicing. For example, exporters may care about their competitors’ prices when they choose their own prices and so they keep these unchanged even when the exchange rate moves. Instead, mark-ups (the difference between the cost of producing the good or service and the selling price) fluctuate in tandem with the exchange rate. For example, Brazilian exporters to the United Kingdom do not necessarily lower the US dollar price they charge for their exports as the Brazilian real depreciates, even though their costs have gone down when measured in US dollars. Moreover, the cost of producing exports may increase to the extent that exporting firms use US dollar-denominated imported inputs in production."

A basic intro-level view of exchange rates would suggest that other countries would often prefer that their own currencies be relatively weaker and the US dollar be relatively stronger. After all, this would make it easier for other countries to export to the US economy. But a stronger US currency also creates financial stresses for other countries. It makes it more costly to repay all those debts that were taken out in US dollars, and it will have a mixture of effects through its effects on previous trade contracts that were invoiced in US dollars. In their empirical work, these authors find that an appreciating US dollar--or conversely, a weakening of the currencies in other countries, is actually associated with less growth. They write:

"We find that periods of US dollar appreciation are typically associated with below-average output growth in the rest of the world, in contrast to the boost we might normally expect through the standard trade channel. This is true for both advanced and emerging market economies."

One should be hesitant about drawing unhedged conclusions that a strong US dollar will necessarily make other countries worse off: there are many other potentially confounding factors going on in the world economy. But these connections do suggest that as the Federal Reserve continues to slowly raise US interest rates, which will tend to make the US dollar more attractive and to increase its value, there may be some unwelcome spillover effects for financial systems in other countries.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest