Comments (2)

John Mcvey

3D printing will change the tech sector forever

Pete Sutcliffe

This is very exciting

There's an old slogan for journalists: "If your mother says she loves you, check it out." The point is not to be too quick to accept what you think you already know.

In a similar spirit, I of course know that the introduction of a printing press with moveable type by to Europe in 1439 by Johannes Gutenberg is often called one of the most important inventions in world history. However, I'm grateful that Jeremiah Dittmar and Skipper Seabold have been checking it out. They have written "Gutenberg’s moving type propelled Europe towards the scientific revolution," for the LSE Business Review (March 19, 2019). It's a nice accessible version of the main findings from their research paper, "New Media and Competition: Printing and Europe'sTransformation after Gutenberg"(Centre for Economic Perfomance Discussion Paper No 1600 January 2019). They write:

"Printing was not only a new technology: it also introduced new forms of competition into European society. Most directly, printing was one of the first industries in which production was organised by for-profit capitalist firms. These firms incurred large fixed costs and competed in highly concentrated local markets. Equally fundamentally – and reflecting this industrial organisation – printing transformed competition in the ‘market for ideas’. Famously, printing was at the heart of the Protestant Reformation, which breached the religious monopoly of the Catholic Church. But printing’s influence on competition among ideas and producers of ideas also propelled Europe towards the scientific revolution.While Gutenberg’s press is widely believed to be one of the most important technologies in history, there is very little evidence on how printing influenced the price of books, labour markets and the production of knowledge – and no research has considered how the economics of printing influenced the use of the technology."

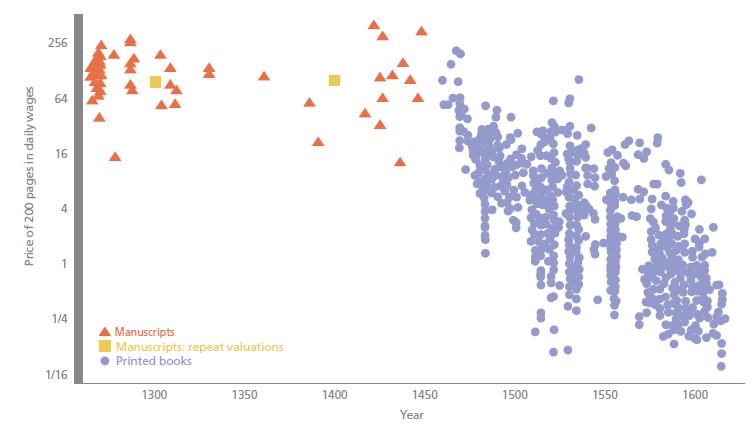

Dittmar and Seabold aim to provide some of this evidence. For example, here's their data on how the price of 200 pages changed over time, measured in terms of daily wages. (Notice that the left-hand axis is a logarithmic graph.) The price of a book went from weeks of daily wages to much less than one day of daily wages.

They write: "Following the introduction of printing, book prices fell steadily. The raw price of books fell by 2.4 per cent a year for over a hundred years after Gutenberg. Taking account of differences in content and the physical characteristics of books, such as formatting, illustrations and the use of multiple ink colours, prices fell by 1.7 per cent a year. ... [I]n places where there was an increase in competition among printers, prices fell swiftly and dramatically. We find that when an additional printing firm entered a given city market, book prices there fell by 25%. The price declines associated with shifting from monopoly to having multiple firms in a market was even larger. Price competition drove printers to compete on non-price dimensions, notably on product differentiation. This had implications for the spread of ideas."

Another part of this change was that books were produced for ordinary people in the language they spoke, not just in Latin. Another part was that wages for professors at universities rose relative to the average worker, and the curriculum of universities shifted toward the scientific subjects of the time like "anatomy, astronomy, medicine and natural philosophy," rather than theology and law.

The ability to print books affected religious debates as well, like the spread of Protestant ideas after Martin Luther circulated his 95 theses criticizing the Catholic Church in 1517.

Printing also affected the spread of technology and business.

Previous economic research has studied the extensive margin of technology diffusion, comparing the development of cities that did and did not have printing in the late 1400s ... Printing provided a new channel for the diffusion of knowledge about business practices. The first mathematics texts printed in Europe were ‘commercial arithmetics’, which provided instruction for merchants. With printing, a business education literature emerged that lowered the costs of knowledge for merchants. The key innovations involved applied mathematics, accounting techniques and cashless payments systems.

The evidence on printing suggests that, indeed, these ideas were associated with significant differences in local economic dynamism and reflected the industrial structure of printing itself. Where competition in the specialist business education press increased, these books became suddenly more widely available and in the historical record, we observe more people making notable achievements in broadly bourgeois careers.

It is impossible to avoid wondering if economic historians in 50 or 100 years will be looking back on the spread of internet technology, and how it affected patterns of technology diffusion, human capital, and social beliefs--and how differing levels of competition in the market may affect these outcomes.

A version of this article first appeared on Conversable Economist.

3D printing will change the tech sector forever

This is very exciting

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest