Comments

- No comments found

When seeking to justify my career as an editor, I sometimes say that my value-added happens through subtraction: that is, if the final version of the paper as it appears in the Journal of Economic Perspectives makes all the same points, but is 8000 words of text instead of 10,000 words, then I have saved time for readers.

It is fairly standard for me to reduce the lengths of first drafts by 20%, although the trims are sometimes much greater. I once cut a first draft that was over 80 pages to less than 20 pages.

Back in the Dark Ages before word-processing, there was a natural incentive to keep papers short: namely, you (or someone) had to retype each draft. But in a word-processing world, there is a tendency to respond to any given concern by adding either a little or a lot. The implicit assumptions behind this approach are that longer explanations are more clear, and that the reader’s time has zero cost.

In fact, there may be a cognitive bias in favor of adding, rather than subtracting. In “People systematically overlook subtractive changes,” Gabrielle S. Adams, Benjamin A. Converse,

Andrew H. Hales and Leidy E. Klotz run a series of experiments to see whether people are more prone to add or subtract in different settings (Nature, April 7, 2021).

For example, one set of experiments shows the players an illustration of a miniature golf hole, and asks them for their suggestions for improvements. Notice that this situation allows for either additions or subtractions. However, some players were told explicitly that they could offer additions or subtractions, while others were not offered any cues. Those who were reminded of the possibility of using subtractions were much more likely to do so.

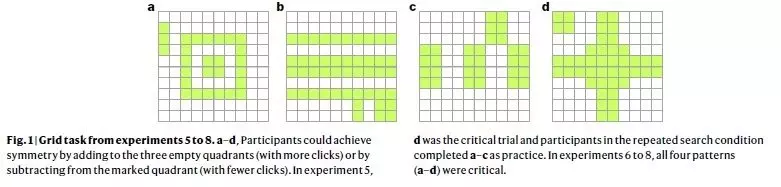

Another set of experiments presented the players with the graphs shown below. The players could click on a white square to turn it green, or a green square to turn it white. The players were supposed to adjust the figure so that it was symmetric both from side to side and from top to bottom. The players were also told that the goal was to create symmetry with as few clicks as possible.

Consider Panel D as one example. One way to create the requested symmetry is to add four green squares to the upper-right, bottom-right, and bottom-left of the figure. Another way is to delete the four green squares in the upper-left. Subtraction requires fewer clicks. But unless people are prompted with the idea that subtraction is a possibility, or unless they have multiple chances to do this kind of puzzle and thus learn from experience, subtraction is a less likely choice.

Or course, extrapolating from these kinds of experiments to broader contexts is fraught with difficulties. But I’ll just say that in my experience as an editor, there’s clearly a bias toward addition. No author ever says: “I have a really hard time adding to my earlier drafts.” Many authors say: “I have a hard time with trimming my earlier drafts.” But even if longer papers are more clear (a proposition that would need some proving), it remains true that the time of readers is limited. One hopes that a given paper has considerably more readers than authors. If that is true, then time spent on subtraction from a given draft will produce an overall savings of time for the economics profession as a whole,

Of course, there are other possible implications of a bias toward addition. Adams, Converse,

Hales and Klotz write:

As with many heuristics, it is possible that defaulting to a search for additive ideas often serves its users well. However, the tendency to overlook subtraction may be implicated in a variety of costly modern trends, including overburdened minds and schedules, increasing red tape in institutions and humanity’s encroachment on the safe operating conditions for life on Earth. If people default to adequate additive transformations—without considering comparable (and sometimes superior) subtractive alternatives—they may be missing opportunities to make their lives more fulfilling, their institutions more effective and their planet more liveable.

Perhaps some of the New Year’s resolutions for 2022 should involve not what you can add to your life or your daily routine or your to-do list, but instead what you can subtract from it.

Timothy Taylor is an American economist. He is managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a quarterly academic journal produced at Macalester College and published by the American Economic Association. Taylor received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Haverford College and a master's degree in economics from Stanford University. At Stanford, he was winner of the award for excellent teaching in a large class (more than 30 students) given by the Associated Students of Stanford University. At Minnesota, he was named a Distinguished Lecturer by the Department of Economics and voted Teacher of the Year by the master's degree students at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Taylor has been a guest speaker for groups of teachers of high school economics, visiting diplomats from eastern Europe, talk-radio shows, and community groups. From 1989 to 1997, Professor Taylor wrote an economics opinion column for the San Jose Mercury-News. He has published multiple lectures on economics through The Teaching Company. With Rudolph Penner and Isabel Sawhill, he is co-author of Updating America's Social Contract (2000), whose first chapter provided an early radical centrist perspective, "An Agenda for the Radical Middle". Taylor is also the author of The Instant Economist: Everything You Need to Know About How the Economy Works, published by the Penguin Group in 2012. The fourth edition of Taylor's Principles of Economics textbook was published by Textbook Media in 2017.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest