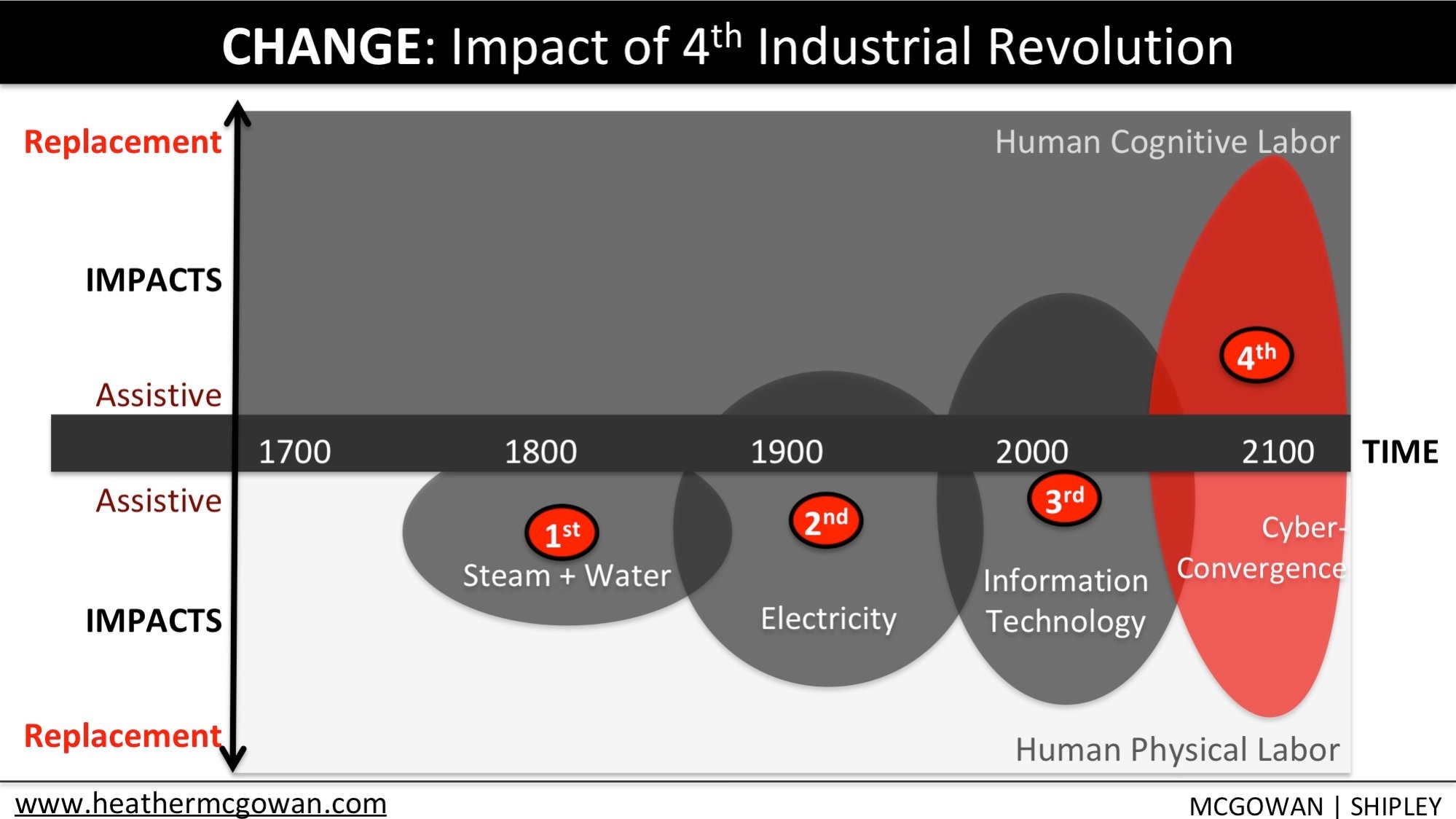

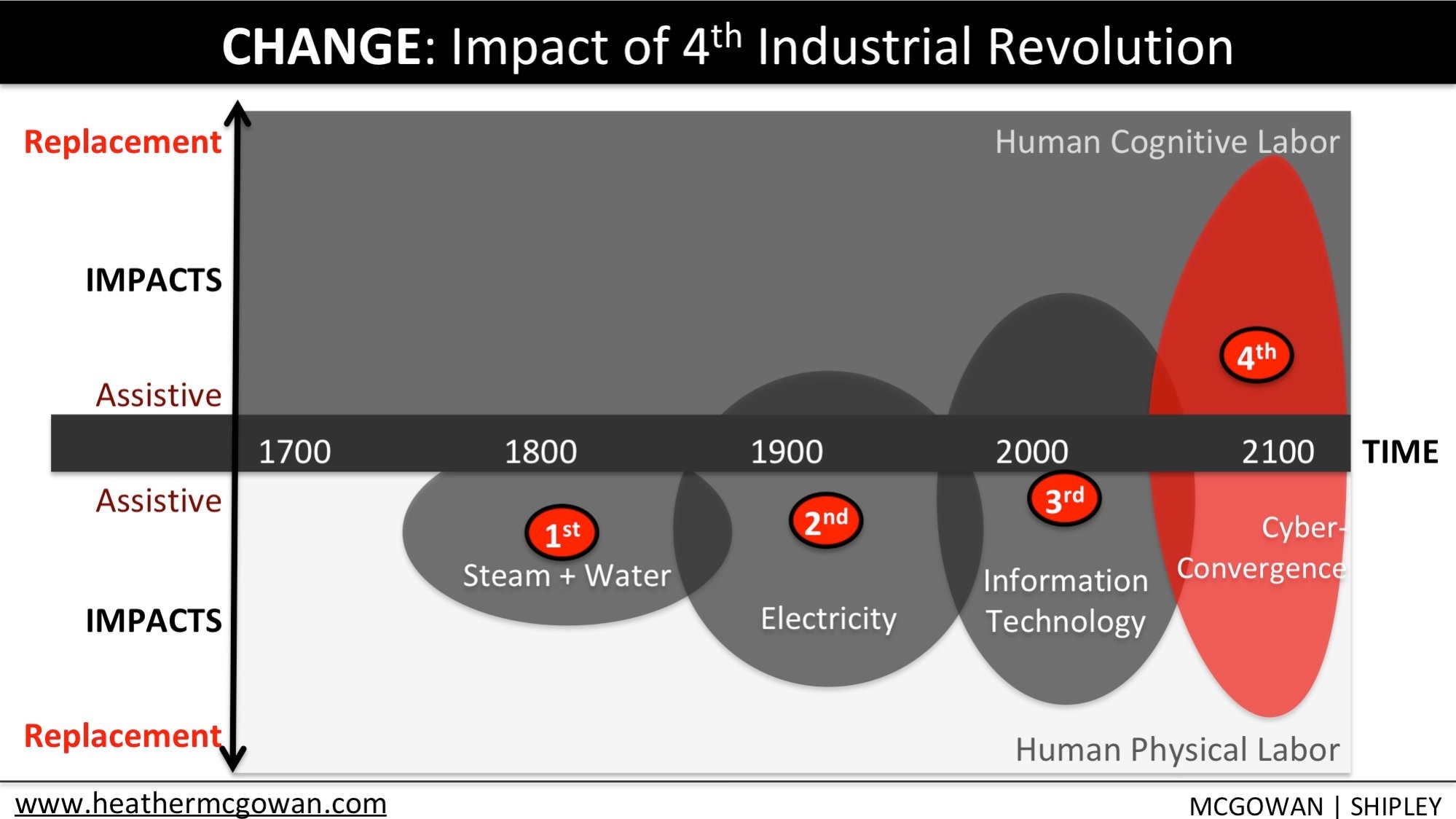

If we look behind us, we can see three industrial revolutions that have occurred over the last 150 years with another right on the horizon as you can see in the figure below from Heather McGowan's The Hard Truth About Lost Jobs: It's Not About Immigration.

In the first revolution, we saw the displacement of millions of workers who moved from the farm to the factory. We are now in a position where fewer than 2% of the American (and Canadian, and European…) workforce is now engaged in producing food, and producing at least 5 times as much (based on calories per person). This change took about 100 years to happen, at which time electricity (as a form of energy) displaced steam and water to usher in the second industrial revolution.

The transition from the first to the second industrial revolution was painful for many, at least at an individual level, but turned out to be a great thing for the vast majority. Following the explosive growth of the number of jobs in the manufacturing sector of the economy there came an explosion in the number of jobs in the area of cognitive services.

The new world of manufacturing and cognitive services fostered a requirement for new skills to drive the revolution. The need for millions with new, highly specialized, manual skills drove the inception and development of a massive college system to fill these needs. The college system also helped meet the ever growing thirst for people trained for basic cognitive service tasks. More complex cognitive service tasks required more education and a corresponding explosion in the number and capacity of universities followed in the mid-1900s. The relatively well paid manufacturing and even higher paid cognitive service sectors made the masses richer. Tens of millions of families benefited and the bulk of the population entered the middle class.

For many years there were two roots to reasonable prosperity, manufacturing for those with little or no education, and cognitive services, for those who obtained higher degrees. I have worked in the university system for decades and I have seen, many times, the glowing pride on the tradesman’s face when his daughter brings her dad up to meet me after a graduation ceremony and he says, in a way that you have to experience to understand, “Susan is the first person in our whole family to ever get a university degree!” Sounds like a simple thing, but for over a hundred years, a degree from a university was the doorway to the upper middle class.

The interesting thing about the second industrial revolution is that, when it began, there was nobody who could foresee where it would lead. What would the millions moving into manufacturing manufacture? What would we ever be able to do with millions of university graduates? Nobody imagined a refrigerator in every kitchen. Transoceanic flying becoming a form of mass transit. New cars that are traded up every five years or so for another one. Who could have foreseen the rise of financial services, huge government bureaucracies, millions of school, college, and university teachers. Millions of highly qualified administrators and others who make sure that the refrigerators can be built, sold, and delivered with well engineered supply and sales departments. The second industrial revolution happened, and the only thing that could be seen at the start was a massive need for trade skills (welders, electricians…) and a variety of cognitive services (accountants, lawyers, administrators…). There was no way anyone would have been able to predict what people with all of these skills would end up doing or making, but it happened anyway.

In the last decade of the last century, the third industrial revolution happened. The information technology revolution happened. The immediate needs, as far as training went, were electronic engineers, code writers, systems managers and others who ushered in the age we live in now. There is no way that anyone could have imagined where we would be fifty years later. How could the engineers who first built ArpaNet have foreseen Google, Apple, or Amazon? All they could see was the same thing that the early pioneers who laid the foundation for the first and second industrial revolutions could see: what they were doing would change the world. They could also clearly see that in order to change the world, certain skills would be needed by those doing the changing.

We are now entering the fourth industrial revolution.

This revolution which, just like those that proceeded it, is being built on the revolutions that proceeded it. We still have food producers, manufacturing, highly skilled manual trades, the need for cognitive services expertise, and information technology workers. However, just like we have seen in the revolutions that came before, we won’t need nearly as many. Just as we can produce all the food we can eat with just 2% of the population, we will soon be manufacturing all the stuff we can use with some other ridiculously low number of workers. Information technology has advanced to where we can replace virtually all routine manual and cognitive tasks with algorithms. The jobs that built the middle class that we are familiar with are disappearing. Most executives today agree that they do not currently have the expertise and skills in their organizations that are needed for a successful transition to this fourth revolution. The transition is painful for all of us from the top of the ladder to the bottom of the rung. Unfortunately, this transition is generating stubbornness and scapegoating galore, but no matter how much more trustworthy a horse was pulling a wagon carrying your family (you can’t get to really know and trust a motorcar like you can a faithful old horse), if you are planning on running a livery stable in today’s world, you won’t make anyone a living.

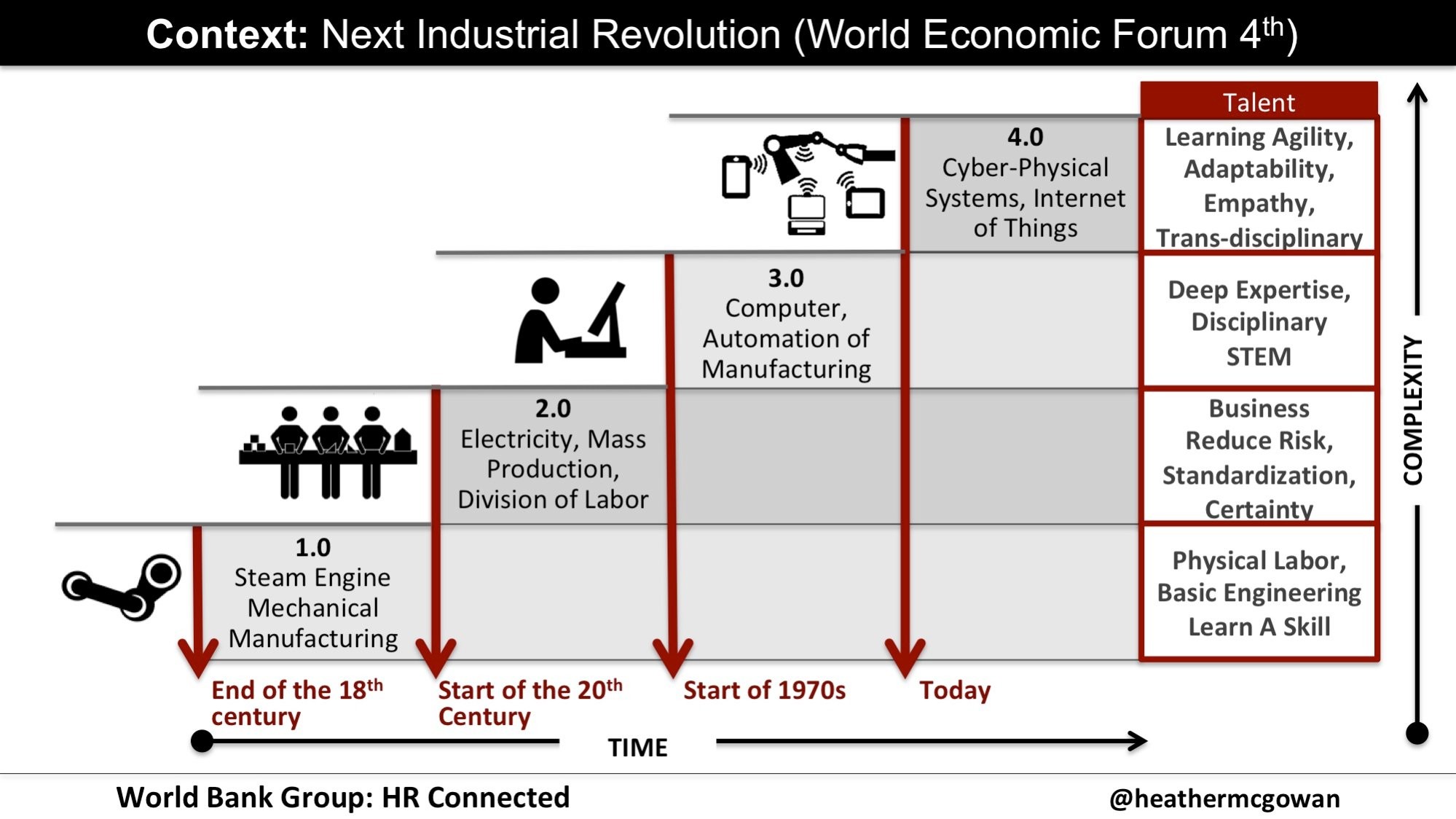

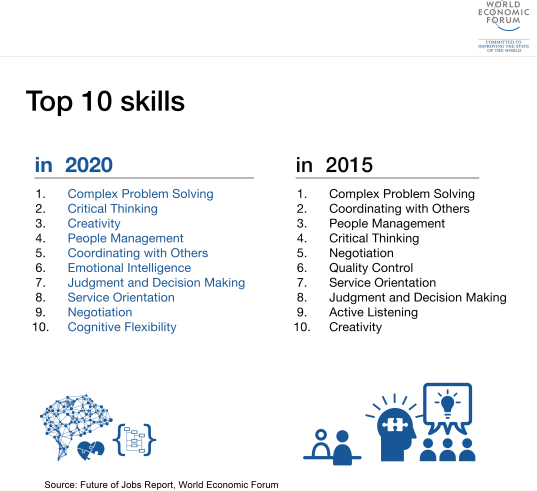

The fourth industrial revolution is currently being called the cyber-physical convergence. There is nobody who can clearly see what is going to emerge from this revolution, but we have a good guess at what skills are going to be required. The World Economic Forum published a list of skills that will be needed in the near future.

As you can see, six of the ten listed in the 2020 column are higher order thinking skills, skills that are not being taught in our current educational systems. Skills that will be the foundation upon which the next iteration of our society will be built on. Skills that will change the world. Skills that, according to the slick marketing campaigns, can be acquired through a weekend seminar or a 99¢ app (like that's really going to happen). Skills that will make us who we are going to be.

We know how these higher order thinking skills are learned, and it isn’t at a weekend seminar. Our current university system is still fixated in providing graduates with the skills necessary for the society that was built on cognitive services. The masses of people, who can see changes coming but don’t know what to do, are demanding more places in universities to gain the cognitive services skills that have served the middle classes for decades, and the higher education institutions are more than happy to expand to meet that demand, and skyrocket the prices as demand exceeds supply.

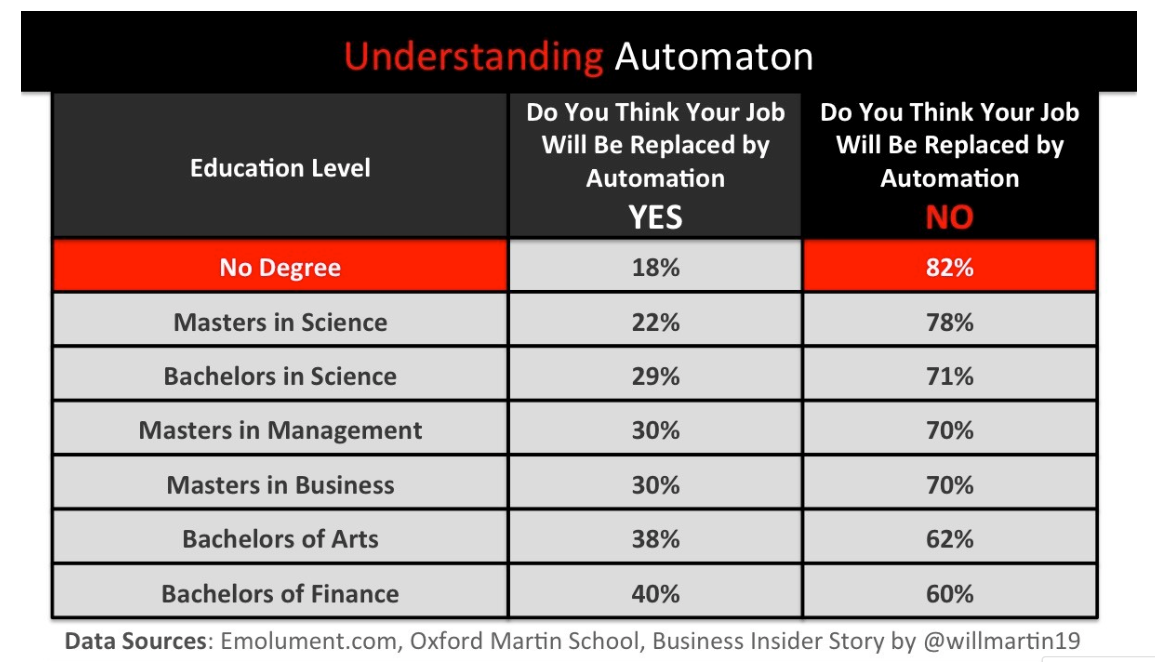

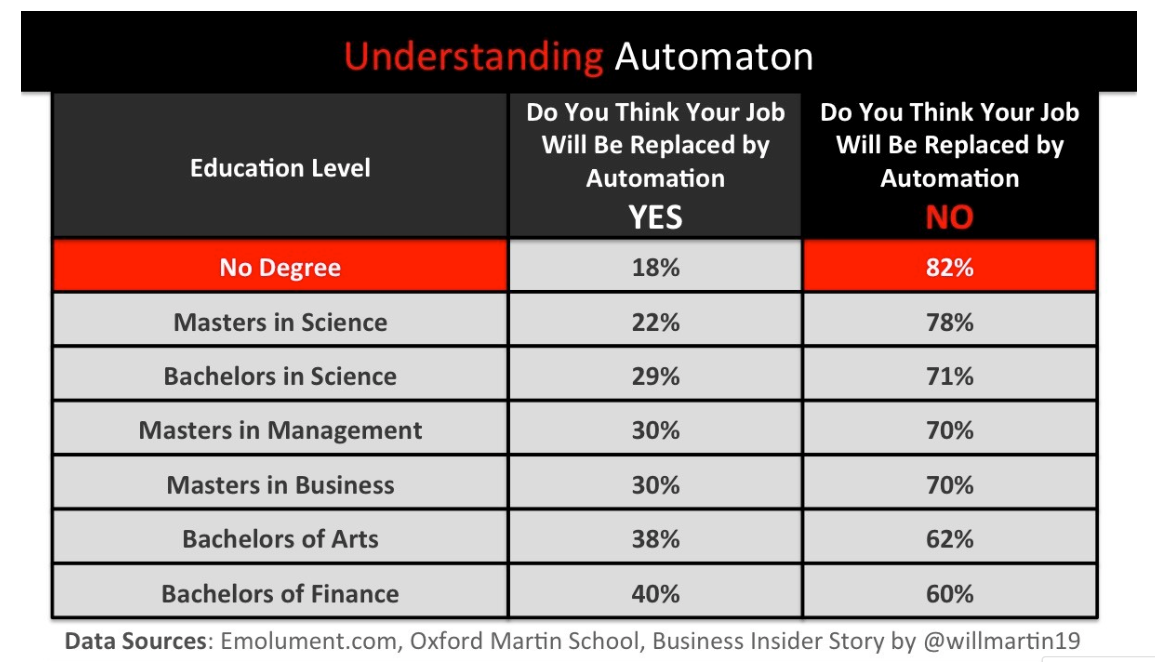

Individuals who have been, are, and are hoping to become successful under the regime that is currently in place are already facing disillusionment when they see that who they are and what they have become is not what is needed to be successful in tomorrow's world. Just like the fellow who couldn’t trust a motorcar, millions swear that they will never trust a driverless vehicle. Maybe they will be right this time and the future will stop coming. They never asked for change and don’t see why they should have to change when things are just fine as they are. This Table from Heather McGowan’s The Hard Truth About Lost Jobs: It's Not About Immigration gives us an idea of just how many insist that the future is not going to happen and it is not going to happen to them.

I was going to add another column with an estimate of how many individuals would embrace the learning of higher order thinking skills as a way to prepare for the future, but after thinking about the table I realized that the numbers are already there. The numbers in the NO column are clearly in that group. If their job isn’t going to automated, why would they need put in the significant time, effort, or money needed to learn these new skills. I would guess that at least 60% or 70% of those in the YES column will miss the mark on their learning needs and opt to engage in learning that will equip them with a different skill set that belong to the society we are leaving behind. Changing from being a blacksmith to owning a livery stable didn’t prepare anyone for the future at the beginning of the last century. Just look at the number of specialist schools that have sprung up to teach coding skills – a skill that, according to Tom Hulme, a general partner in the venture capital arm of Google parent firm Alphabet, is on the cusp of being done by deep AI.

I would be willing to bet that the children of the 1% who control half of the wealth in the world are not going to trained in a skill set needed for yesterday’s world.

The world is changing.

Just as steam and water fundamentally changed production, the first revolution changed learning from cottage based family traditions to apprenticeships. With the advent of the second revolution, colleges supplanted apprenticeships as a better way to learn the skills necessary to drive the new skilled trades and cognitive service needs. Universities exploded in numbers and capacity as the third industrial revolution got underway and the need for a more sophisticated skill set that included cognitive skills, computer skills, and interpersonal skills was met by a new provision for learning.

As these new methods of delivering the learning that were needed in the societies of the time, that didn’t mean that the method that preceded it was wrong, it simply meant that the needs for the new revolution couldn’t be met by the methods that were already in place. After studying, writing about, and banging on the doors of higher education for years in an effort to bring about change in order to meet the needs of the next generation of learners, there is not only no will to change, but the direction being taken is a deeper entrenchment of the status quo. The traditional education system isn’t going change to meet the needs for the skill set needed for tomorrow’s world.

So, what will?

I see a learning system that will arise based on the technologies that are forming the basis for the fourth industrial revolution. I believe that learning will play a central role throughout our lives, and the basic foundation will focus almost entirely on the general higher order thinking skills. The skills that teach us how to think, be creative, keep an open mind about what is going on around us, and provide us with the self awareness to know what we need to know and do to succeed.

The emerging learning environment will be much more personalized and motivating. Hard work, but the kind of work that is satisfying and enjoyable. Credits and qualifications will give way to personalized statements of learning written by teachers and mentors focussed on nothing but the development of thinking skills for their students. How can you figure out what a B+ in creativity means? I can write you a paragraph or two about how my student is doing at mastering the various aspects of critical thinking, the most powerful problem solving tool there is – as long as I actually know my student and care about their development and growth.

There will still be institutions where students will go to master these skills, but there won’t be desks or classrooms. Iterative discussions taking place both online and face to face provide an ideal method of fostering higher order thinking skills. Longer term work on real world problems provides real motivation for learning and opportunities to practice thinking. Lectures will be very occasional and be more akin to keynote addresses. The learning will not involve the memorizing of anything – students have smartphones for that. The learning will involve solving real world problems in a variety of contexts.

Clear guidelines will be provided to map out an ideal program to best learn and master these thinking skills, and students will enter and exit this initial formalized part of their lifelong pursuit of learning based on their individual priorities and satisfaction - definately not a factory based system.

Learning these skills will require whatever technology we have available at the time that will serve learning. In the world today, the technology comes first with thousands looking for a way that any new technology that appears can be pushed into education. We need to put the learning first and look for technology that enhances learning and not for educational marketing opportunities that can sell technology.

Prohibitively expensive? Yes! However, consider the cost to the individual 300 years ago when an apprenticeship was entered into. In most cases, years of work for nothing more than room and board – now that’s expensive. Or, the price of college to someone just leaving a farming lifestyle. And, the current cost (presently skyrocketing) of a “good” university education. With every industrial revolution, there has been a corresponding learning revolution that, at the time, looked prohibitively expensive. However, the cost of maintaining the status quo in the past was the cost of missed opportunity which, in many cases, was a fortune. If we really believe that the skills required for the next industrial revolution are higher order thinking skills the we have to be willing to pay the real cost associated with acquiring them – don’t be sucked in by the $4.99 brain training app. The cost of missing the next revolution's learning opportunities will be as high as clinging to the traditional way of doing things was in the past.

A different vision of learning, but a vision based on what we know about learning (based on The Science of Learning) as opposed to what we know about teaching. A vision that enables anyone to reach their fullest potential as opposed to enforced conformity and authoritarianism that we currently see in an effort to meet the needs of the past. A vision that will open the doors to endless possibilities rather than simply the probability of memorizing what we already know and regurgitating it for a grade thereby demonstrating that we can engage in routine cognitive tasks.

A vision for the future.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest