Comments

- No comments found

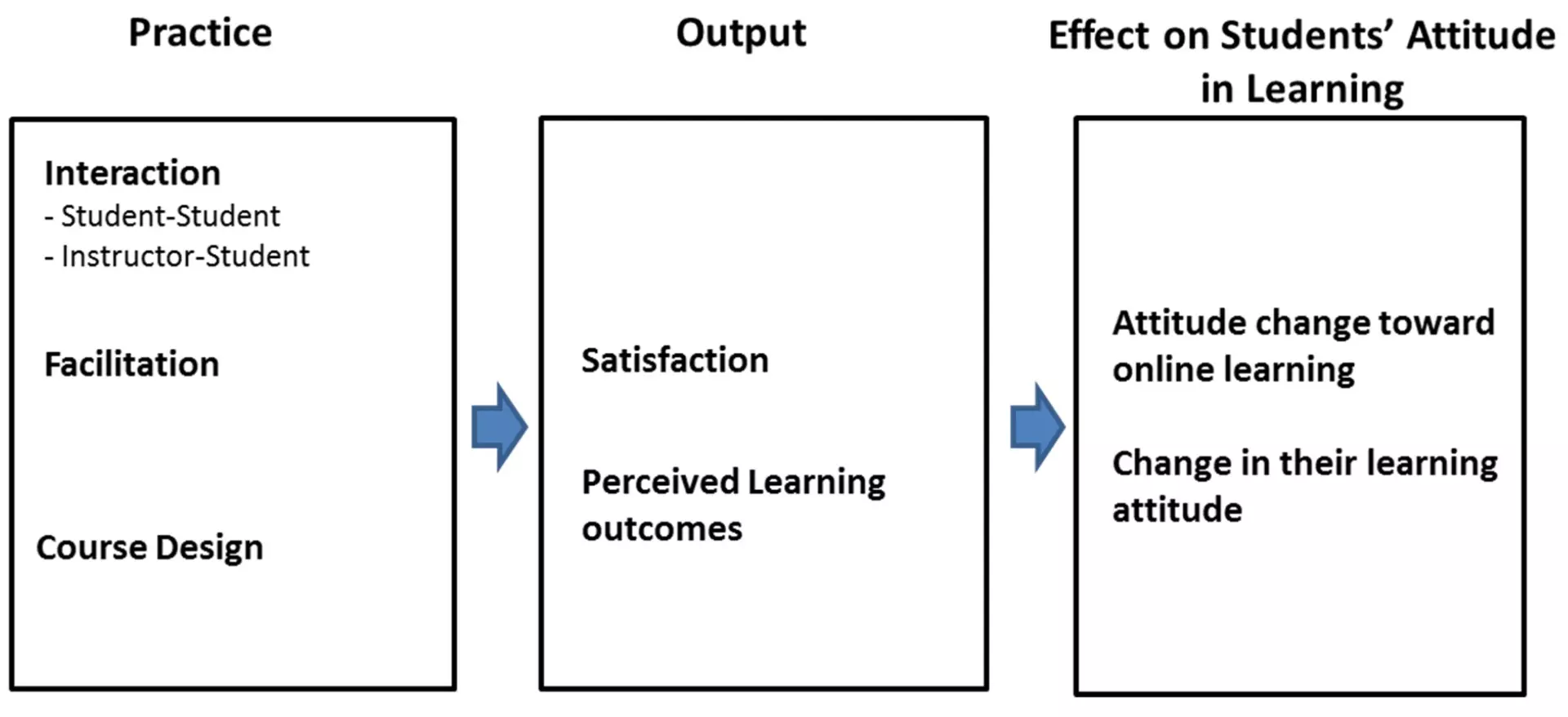

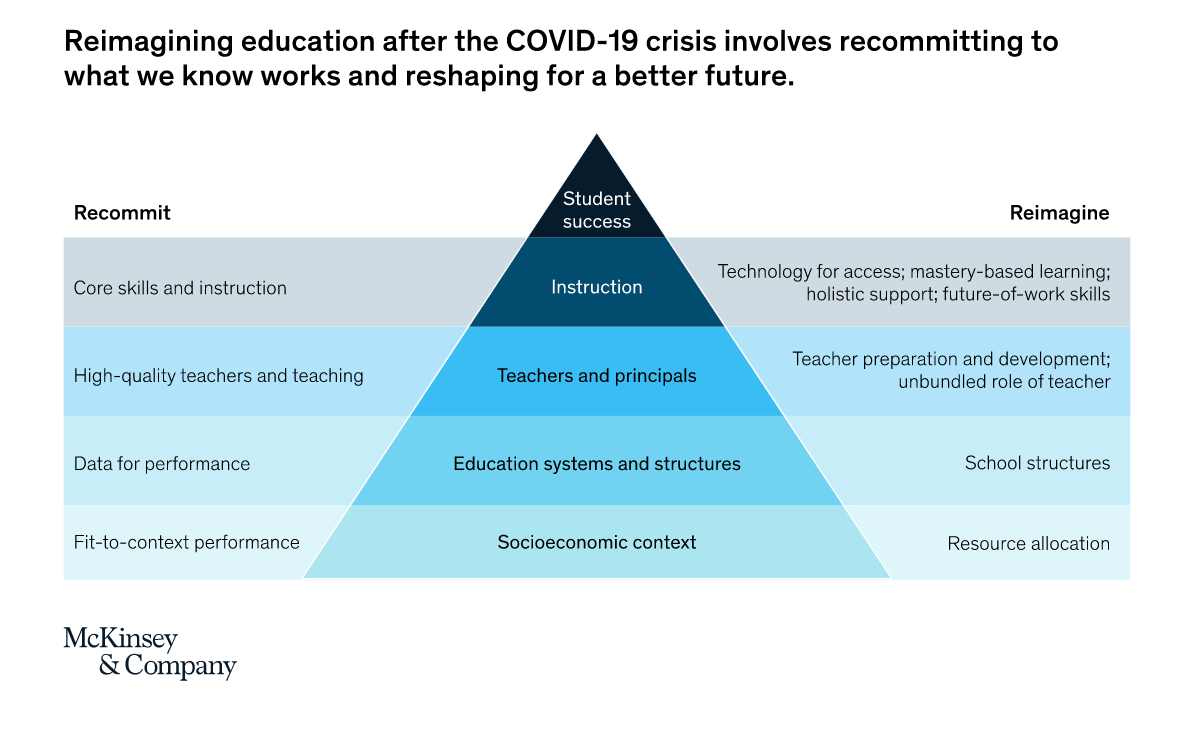

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in nearly all schools switching to a hybrid format.

Student's attitude towards learning is changing post pandemic preferring a mix between online and in-person classes.

We often feel that our students arrive at our higher education institutions not caring and with a single focus, grades leading to a qualification.

In fact, that is actually the case. The 2021 intake of students, 85% of the students had, as their first priority in higher education, to get a good degree that will get them a good job when they finish.

There are numerous articles written about the generation X, Y, or Z students as well as the millenials who have and are arriving at our institutions. There is a constant moaning that they do nothing more than we ask, they are not interested in learning, they have no initiative when it comes to learning, they are unprepared for university or college, they expect hand-holding, and they exhibit an attitude of complete entitlement. The list could go on and on, but all of you know exactly what I mean. It doesn’t matter whether you have said it or even agree with it, that is the attitude of many teachers in higher education. Let’s consider some of these students' attitudes.

For most of the items on the above list, they are arriving in our institutions doing and acting exactly as they have been trained to do and act throughout their entire educational experience. Common Core (or whatever it is called in your country), standardized testing, teaching to the test, meeting the educational standards for conformity and on and on. This has been their experience since they entered the first grade. This is their expectation for what education is all about. They know nothing more than, “Your job is to tell me exactly what is on the test so I can pass it.”

We can blame the school teachers if we want, but the fault lies with the system. Research has demonstrated that the primary purpose to which the results of standardized tests are put is to measure the performance of the schools. The funding model is such that schools that perform well receive additional funding. The school administrators from top to bottom, as well as the teachers themselves, are focussed entirely on doing well on the tests. How can we blame any of them for doing their jobs well?

My daughter asked me to tutor my granddaughter in math so that she could increase her grades. I was stunned to see how the system worked in their high school, and which I can imagine is similar anywhere standardized testing is in place. The students are given regular unit tests – something I remember doing back in the unenlightened pre-standardized testing era. What I was stunned about was that she could take the exact tests and do the exact worksheets over and over and over again, for credit, just so she would be able to answer the questions correctly on the upcoming standardized test.

That isn’t how I teach to learn. We never had a single problem during our tutoring sessions. All we talked about were the principles behind the problems. Looking carefully into the why behind the concepts, my daughter said to me one day that my granddaughter had told her that she loved her tutoring sessions with me because I made learning her math so easy. We didn’t go over any problems – and her grade improved from Fs and Ds, to As and Bs.

When our students arrive in our institutions, they are looking for proper teaching, which in their minds means telling them exactly what they need to know in order to pass the test. How many times have you been asked, “Will this be on the test?” What they really want to know is, “Do I have to learn this for a test, because I’m not going to do anything more than I absolutely have to do in order to get by.” There is nothing unusual here. Anyone who has spent more than five minutes with teenagers and young adults knows that their time is precious. Time to be spent doing important (to them) things like gaming, social media, in person socializing and on and on. We were no different, we just didn’t have the tools, and (here is the crux) more was expected of us in higher education.

What does this have to do with us? I’ve just stated the obvious, something we all know and grit our teeth at when we think that in just over a month, we start over again. What it has to do with us is that we are complicit in perpetuating all of the above. Of course the students whine and complain when we ask for more than that, but we don’t have to concede – unless, of course, you have a department head, in an unnamed local college, who told me that my primary job was to keep the students happy and give them what they want (I won’t teach there any more).

The students feel entitled because that is all that they have had. We support their feelings of entitlement by continuing in that tradition. Students will find the classes where the load is light and the grades are easy, and they will design their programs with those parameters as their primary guides. Who is to blame them for that?

Every year I’m teaching the way I do, with the students doing all the work and me getting all the credit, I start out with some predetermined number of students (60, 80, 120 – whatever) and I begin, weeks before the class begins, sending them out instructions telling them what they have to do (I’m talking about second, third, and fourth year classes). I have their talk schedule for the semester published at that time, and a quarter of them will be scheduled to give talks on the second day of class with the added insult of having to produce their first assignment (a 500 word evidenced piece as well as five evidenced comments on each other’s work) by the end of the first week. By the time I reach the third week of classes (beginning at least a month before classes start), I will have lost a third of the students about three times – a third drop with new students filling their spaces, and of the new third, a third of them drop again with this happening over and over until the numbers settle in about the third week of classes. Because I have such high rankings both on “rate my professor” and among the student culture, there is always a waiting list a mile long of students trying to get into my class.

Those who stay in my class go on and on and on about how brilliant the class is. Why? Because, in their own words, they had no idea that learning and thinking, real learning and thinking, could be so much fun! They have never experienced it before, and they love every minute of it. The only lecture I give is the day one lecture when I tell them what they will be doing for the semester. From then on, they do all the work. And they tell me that my class is by far the hardest, most time-consuming class they have ever taken. One student reported that she dropped two other classes in the semester that she took my class because the overall workload was too much – but she stayed with my class. It isn’t because I’m brilliant at pontificating because I don’t do that, it is because they really want to learn, they’ve just never been given the chance. In a way, I cheat because I also use all that I know about The Science of Learning to maximize their experience.

The students, at least the ones who stay with me, want to learn. They want to learn to think. I am certain that most of the rest of us would react in exactly the same way if it wasn’t new and different from what they were used to. And the rest, who just want to do the minimum for the grade and qualification – they shouldn’t even be there. I know that this kind of attitude goes against what every administrator in higher education believes, but that is where I stand.

Your students don’t have to continue with the attitude they arrive with. Not if you choose not to reinforce what they expect and what they have always done. Try it, you may like it.

Jesse is a world leader in the integration of the science of learning into formal teaching settings. He is an Adjunct Associate Professor at the University of Lethbridge and Director at The Academy for the Scholarship of Learning. Huge advocate of the science of learning, he provides people with ideas about how they can use it in their classrooms. Jesse holds a PhD in Psychology from the University of Wales, Bangor.

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest